Trapped in the Gangs Matrix

The Gangs Matrix is a racially biased database criminalising a generation of young black men. Some have never even committed a serious offence before, but still find themselves stigmatised and targeted by the police.

‘If you’re black and born on an estate, nowadays the system automatically sees you as being in a gang.'

Stafford Scott, The Monitoring Group (Tottenham)

Violent crime has blighted the UK’s capital, and the Gangs Matrix was created in an attempt to tackle this serious problem and protect communities.

However, in reality the Matrix overwhelmingly targets young black men.

They are often labelled as suspected gang members based on weak indicators – sometimes simply because they’ve been victims of gang violence themselves. Or for reasons as trivial as the music they listen to and the videos they watch online.

Young. Black. Male. ?This is all it can take to end up on @MetPoliceUK’s Gangs Matrix. Call on @SadiqKhan to urgently review this broken system: https://t.co/M20gej1Pzy pic.twitter.com/bbVDPVlfLv

— Amnesty UK (@AmnestyUK) May 9, 2018

Worse still, the Met Police are interfering with young people’s privacy rights by sharing this data with other authorities.

As a result, some of those on the Matrix can find it more difficult to access housing, education and employment.

In one case, a young person lost his place in college after they found out the police had him listed as gang-involved.

In another particularly harrowing example, a family received a letter threatening eviction from their home if their son didn’t cease his involvement with gangs, only to have to inform the police that their son had been dead for more than a year.

A deeply flawed system

There is currently a lack of clarity from the Met Police on what a gang actually is, and who is or is not a gang member.

Yet for years, the Metropolitan Police have compiled a list of individuals in response to the 2011 London riots, giving them a ‘violence ranking’ from green, to amber and red.

As of October 2017, nearly 4,000 people were on the Matrix. The demographics of those on the database raises deep concerns. 78% are black, but in reality black people are responsible for just 27% of serious youth crime. Some may never have committed a violent or serious offence.

‘Gangs are, for the most part, a complete red herring… fixation with the term is unhelpful at every level. A huge amount of time, effort and energy has been wasted on trying to define what a gang is when it wasn’t necessarily relevant to what we’re seeing on the streets.’

Senior member of the Metropolitan Police Service, October 2017

What’s more, the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) found that more than 80% of all knife-crime incidents resulting in injury to a victim under 25 in London were deemed to be non-gang related.

Dragged deeper into the system

In part, the purpose of the Gangs Matrix is used as a policing and prosecuting tool, and often informs police decisions about where to exercise stop and search powers.

As a result, individuals on the Matrix are subject to chronic over-policing. In fact, black people are six times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people.

Consequently, individuals on the Matrix are more likely to get picked up and charged for minor offences, dragging them deeper into the criminal justice system.

Targeted for a YouTube video

‘The idea that I’m in a music video and because of that I am affiliated with a gang, that is ludicrous.’

A 17-year-old boy from Hackney, east London

Shockingly, the reason people end up on the Matrix can be as arbitrary as the kind of music they listen to, which YouTube videos they share and their other social media habits.

Police have even been known to set up fake online profiles and covertly befriend people to monitor them - a practice that is in breach of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA).

‘We are not dealing with fact, it’s feeling, it’s “I don’t like what’s happening here”.’

An anonymous official from a London borough gang unit

It is clear that many people are being profiled based on factors that have nothing to do with serious offending, but rather on indicators of youth culture. This is nothing less than a reckless and counter-productive approach to policing.

Damaging life chances

Not only does this data collection interfere with their right to privacy, but the consequences can be serious and life-changing for those listed on the Matrix.

We have evidence that the police sometimes share the Matrix with local non-police agencies such as Job Centres, Housing Associations and schools. In some cases, this can lead to devastating impacts on people’s working and living arrangements because they are listed as a ‘gang nominal’, a label which is vague and stigmatising.

A former housing officer described to us the issuing of eviction notices as a routine tactic used to put pressure on those on the Matrix, which can negatively affect the family members they live with too.

Discriminatory and harmful

This approach to policing varies from borough to borough in London, and it is not effective for ensuring community safety.

Violence and knife crime are receiving a lot of public attention at the moment - and it is clearly a problem that needs to be tackled before more lives are lost. But a discriminatory, and harmful database that violates the rights of young, black men is not the way to go about it. The communities that are most affected by serious youth violence feel that the Matrix is just another tool which demonises and punishes their young people, pushing them further into the criminal justice system not drawing them away from it.

Omar's story

Omar had recently graduated from a course in Sustainable Leadership in Business at Cambridge University in 2012 when his mother received a threatening letter from the Metropolitan Police.

‘It was one of those template letters,’ Omar explains. ‘The (London Metropolitan Police) send them round. It said something like ‘your son is involved in gang activity and if he continues we have the power to evict you from your house.'

Omar was no longer living at home. In fact, he and his family had moved away from Wandsworth borough, the area where he had grown up.

In 2008 he was convicted for possession with intent to supply class A drugs and spent two years in prison. But since being released, he had moved on with his life.

By now he was 22 and living partly in Cambridge for his studies, while working to set up a social enterprise that aimed to reduce reoffending and inspire young people in inner city London. His family had relocated to Wimbledon where they rented a house privately, and he lived there when not in Cambridge.

But the Met Police still had Omar listed as part of a gang in Wandsworth, and had his family’s new address on file. He told his mentor and employer about the letter.

‘My employers at the time contacted them saying how dare they send the letter. He pointed out that I was doing charitable work, enrolled in a postgraduate course at Cambridge. The police responded ‘that your name is in the system and it was sent out automatically’ and they apologised’.

It was not the first time his alleged ‘gang status’ had intruded on his fresh start. One year earlier, his family’s home had been raided by the police as part of a gang enforcement operation led by Wandsworth Borough. The police handcuffed his mother, father and younger sister (Omar was not living at home) and tried to ‘recall’ him to prison, something they could do given that he was still on license for his previous offence.

However, his probation officer opposed it, explaining that there was no evidence to indicate he was involved in any criminal behaviour. He was required to sign in at the Wandsworth police station every day, meaning he could no longer live in Cambridge.

‘They ordered me to sign in at the police station every day in Wandsworth so I used to have to drive every day at six am to get to Cambridge for my lectures because I couldn’t stay in the College. The crazy thing is I was not even associated with the area in any way shape or form. I had completely moved away. If they were doing their job properly they would have found out there was no way this is the right thing to do. Even my probation officer fought my corner and said I was complying with all the terms of my license. After 3 months, they simply said no further action was required.’

Omar’s is just one of many stories we have heard in recent months while researching the Metropolitan Police Service’s data collection on London gangs.

What we are doing

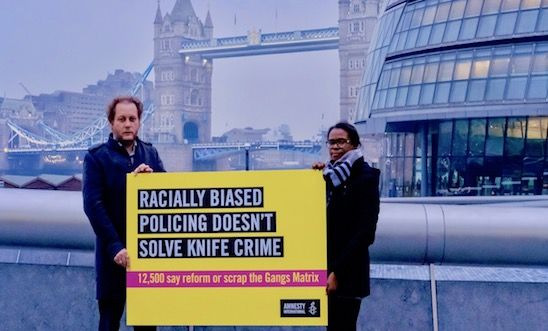

In November 2018, we handed in our petition signed by 12,500 people to City Hall calling on them to review the Matrix and either reform it so it complies with human rights laws or scrap it. We will continue to keep up the pressure until we see change.

Because of the evidence we uncovered, the Information Commissioner's Office launched their own investigation and found the Matrix broke data protection rules.