Hate crimes in the UK – the victims’ stories

Every year hundreds of thousands of people in the United Kingdom are attacked and harassed – physically or verbally – because they are perceived as ‘different’. Why? Perhaps it’s because of their religion or their sexuality, or it’s the colour of their skin, their gender identity or their disability – or a combination of these.

Hate crimes are hugely under-reported, and often inadequately dealt with by the authorities, so we wanted to tell these stories ourselves.

We make no apology for repeating the utterly vile comments they have had to face. They are but a small example of the sort of very real hostility many people deal with every day.

Bijan

Bijan Ebrahimi was an Iranian refugee who had learning difficulties and a physical impairment. Described as a quiet man who loved his garden and his tabby cat, he was subjected to years of harassment and abuse from people on the estate he lived on. Tired of seeing his flowerpots vandalised he decided to take photographs of the young people who gathered outside his flat. Bijan thought that if he collected evidence of the anti-social behaviour the local council would move him to a safer location. Instead, he was branded a ‘paedophile’ by a group on the estate for taking photos.

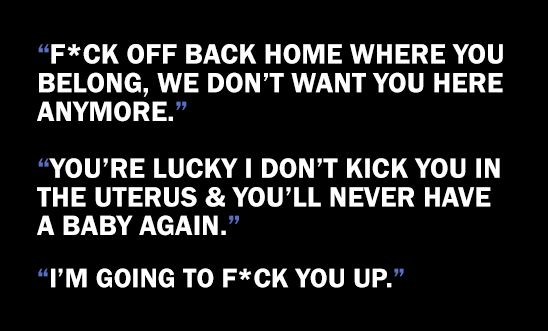

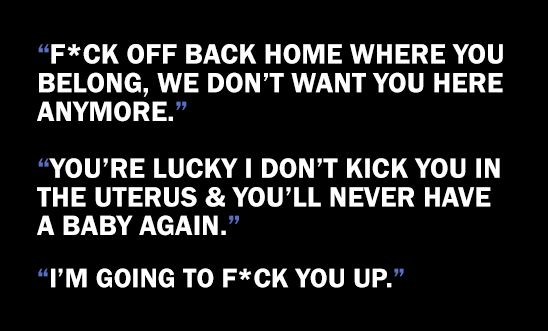

On the evening of 11 July 2013 Bijan saw a neighbour drinking a can of beer in front of his flat and he decided to film him. The neighbour misinterpreted this action as Bijan taking pictures of his daughter, and forced his way into Bijan’s flat shouting “I’m going to fuck you up.” Terrified, Bijan dialled 999 and told the operator that he had been physically assaulted and racially abused. The call was flagged as a hate crime and categorised as a ‘grade one’ incident requiring an immediate response.

By the time the police arrived an angry mob of around 15 people had gathered. Rather than arresting the neighbour, the police detained Bijan for breach of the peace. As Bijan was led away the crowd cheered and chanted “paedophile”. Despite the police logging their concern about the possibility of retribution, Bijan was released from custody the next day. Over the next two days Bijan contacted the police on numerous occasions by telephone and email, stating that his life was in danger. Bijan made his final call to the police at 12.12am on Sunday 14 July, and in the hour that followed the neighbour, with the help of an accomplice, beat Bijan unconscious, dragged his body outside and set it alight.

During the six years leading up to his death, Bijan had many interactions with police community support officers, police officers and police staff as a victim of racist and disablist hate crime. Bijan was regarded as antagonistic and troublemaking’, a ‘pest’, an ‘idiot’ and a ‘pain in the ass’ and this antipathy clearly affected how the police responded to him when he needed them most. The police force failed to protect someone who was extremely vulnerable.

Although the neighbour pleaded guilty to murder and was handed a life sentence with a minimum term of 18 years, the court failed to recognise the disability hostility that many campaigners felt motivated the attack. The court failed to use the enhanced sentencing powers provided by the Criminal Justice Act 2003. The prosecution found no evidence of hostility towards Bijan’s disability when the offence was committed.

Cathleen

"Historically the police and other authorities have been prejudiced towards LGBT people and this has prevented LGBT people from reporting."

For Cathleen Lauder being stared at, talked about and harassed because she is a transgender woman is part of everyday life. She has been subjected to verbal abuse, intimidation and unwanted physical contact ever since she transitioned. She never felt confident enough to report the abuse: she had no proof, and she was concerned about how the police would respond. But then a friend bought her a mobile phone so she could record hate crimes when they happened.

In April 2015 Cathleen was on a bus in Edinburgh when two men and a woman started calling her names, singing offensive songs and making rude gestures at her. Trapped in a small space and worried that the abuse could escalate, Cathleen began recording on her phone. She got off the bus as soon as possible. It was only at the police station, as she was giving her statement, that she realised how much the incident had affected her.

This time Cathleen could provide evidence, and the Crown Office and the Procurator Fiscal decided to prosecute one of the perpetrators. A court date was set for December 2015. Cathleen dreaded having to appear in front of a jury, but she welcomed the opportunity to receive justice. It was a shock to find the court hearing cancelled because the evidence had been lost. She had to wait another eight months for her case to be heard.

Cathleen had experienced persistent, ‘low-level’ hate crime for two years, and when at last she had the confidence to report it, the workings of the criminal justice system brought additional trauma and frustration. “I think there’s still a lot of mistrust between trans people and the police,” she says. “Historically the police and other authorities have been prejudiced towards LGBT people and this has prevented LGBT people from reporting… It is only through better community engagement and training that things will improve.”

Since the court case, Police Scotland have set up a network of LGBTI liaison officers trained by the Equality Network, a Scottish LGBTI charity. It will be important to monitor how this improves the confidence of LGBTI people in the police.

Hanane

In October 2015 Hanane Yakoubi, who was 34 weeks pregnant, was travelling on a bus in London with her two-year-old child and two friends. Another passenger, started berating Hanane and her friends for not speaking English.

For five minutes the perpetrator spouted a vile barrage of abuse, calling the women “sand rats” and “ISIS bitches”, accusing them of supporting Islamic State and hiding bombs in their clothing. She declared: “I don’t fucking like you people because you’re fucking rude. You come to England and you have no fucking manners… Go back to your fucking country where they’re bombing every day. Don’t come to this country where we’re free… You’re lucky I don’t kick you in the uterus and you’ll never have a baby again”.

No one on the bus intervened, but one passenger filmed the attack on a mobile phone and uploaded it to Facebook, where it went viral. After the perpetrator saw the footage, she handed herself in to police. After pleading guilty to causing racially aggravated distress she was sentenced to 16 weeks in prison, suspended for 18 months, and 60 weeks of unpaid work.

Monique (not her real name)

Monique and her children, originally from Ghana, have lived in the UK for approximately 10 years. They initially settled in well in the West Midlands. The children learned English quickly and their immediate neighbours were welcoming. Monique found a job working at a local school and was happy with her decision to come to the UK to provide a better life for her family.

Things began to change in the weeks before the EU referendum in June 2016. The children experienced racist hostility at school, and were told by other children that they would be kicked out of the country. The bullying had a huge impact on their emotional wellbeing -- they became withdrawn and it affected their confidence both at school and at home.

Fortunately the school welcomed intervention from the local hate crime partnership that was already providing the family with emotional support. Workshops about bullying and its impact were delivered to several classes and that, coupled with disciplinary action taken by the school, not only helped to diffuse the situation but also helped Monique’s children to overcome their ordeal.

However, once the EU referendum result was revealed the family suffered further hate crime. For the first time since coming to the UK Monique experienced explicit racist abuse. She was called ‘Nigger’ and ‘Wog’ and on one occasion was spat at and told to ‘Fuck off back home where you belong, we don’t want you here anymore’. Monique began to lose faith in the friendships that she had developed over the years. She grew increasingly anxious, stopped going out on her own and lost her job because her physical health had deteriorated.

The racist abuse that Monique and her family experienced cannot be detached from the toxic political climate that was created in the weeks leading up to the EU referendum.

The issue of immigration dominated political speeches and front pages, and in turn the scaremongering fuelled and legitimised hostility towards minority ethnic and faith communities. Monique, along with the thousands of other victims who experienced pre- and post-Brexit hate, were failed by some politicians who stoked up fear and hatred for political gain.

After initially trying to ignore the abuse, Monique decided to report the incidents to the police. She felt her victimisation was dismissed by officers because she had not reported the incidents at the time in which they happened. Monique continued to report hate crimes as and when she experienced them but, again, she was disappointed by the response she received. On multiple occasions Monique was visited by police community support officers who told her that they could not investigate the hate crimes because there were no independent witnesses. The police failed in their duty because they did not take Monique’s statement or even try to collect any evidence such as CCTV footage. As a result of her victimisation and her experience with the police, Monique has been left feeling isolated, unwanted and worthless.

Paul

"I am being attacked because of my sexual orientation... I cannot take much more."

In January 2015 Paul Finlay-Dickinson lost his long-term partner Maurice to cancer but was unable to fully grieve his death because he was being harassed and threatened by local youths. In the 18 months leading up to Maurice’s death, the couple were regularly subjected to homophobic abuse, their house was vandalised and faeces was pushed through their front door. The torment continued when a memorial card announcing Paul’s death was posted to the house and opened by Maurice who was terminally ill at this stage. Even the rainbow flag that Maurice had wanted draped on his coffin was defaced with faeces.

After Maurice died, and with the homophobic attacks unrelenting, Paul felt that he could no longer live in his north Belfast home. In June 2015 Paul was getting ready to move into a new house, which he thought would bring an end to the harassment that he had endured for so long. However, before Paul could move in to the property a group of young people smashed the windows and daubed ‘pedo’ beside the front door. Paul was too afraid to move in. “I am being attacked because of my sexual orientation”, he said. “I cannot take much more”.

Homophobia is still widespread in Northern Ireland and gay rights campaigners have expressed concern that politicians and faith community leaders continue to reinforce prejudiced attitudes towards gay people. Some political and religious leaders in Northern Ireland have regularly referred to same sex relationships and to gay people as ‘sinful’, ‘evil’, an ‘abomination’ and ‘intrinsically disordered’. This discourse has helped to create a climate in which homophobic hostility is seen as acceptable and legitimate.

How we change things

It goes without saying that hate crimes can cause lasting physical and emotional damage. They can evoke despair, anger, and anxiety in victims, and they spread fear and mistrust in communities thus weakening the social glue that binds a society together.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Authorities across the UK must do more to tackle hate crimes and engage proactively with communities.

Police forces must also be adequately trained to correctly identify hate crime, and in how to respond to and support victims appropriately.

Finally, there must be an extensive review of the hate crime legal framework within the UK to assess whether the current system meets the needs of hate crime victims.

With many thanks to the University of Leicester, who produced the report from which our briefing is based on – see more here.

Our blogs are written by Amnesty International staff, volunteers and other interested individuals, to encourage debate around human rights issues. They do not necessarily represent the views of Amnesty International.

I've never had any abusive comment thrown at me, but it makes mee sick reading these, knowing that some people are actually like this

I see all the changes taking place in the world, sadly hatred & racism erupting to the surface. I feel the pain of my nation as it regresses into something I don't understand, or feel in my heart. I feel the pain of humanity, the world has truly gone mad! I would never be a bystander if I witnessed any form of discrimination, racism, hatred of any kind or form. I am a Global Citizen, and the world is my country. Amen

I have a lifetime of extensive familiarity with this sort of speech and attitude myself, growing up in a declining working-class town since the 1960s. Significantly, it is massively less prevalent here now as people have become interconnected and attitudes have shifted accordingly, and yet we see plenty of it still particularly in outlying areas where there is far less of a racial or cultural mix, although this must never, ever be taken as ill-considered stereotypical prejudice against either all or any folks from such areas. I am fortunate thus to be neither pessimistic nor complacent; both of those attitudes being likely to inhibit action against ignorance-based resentment and prejudice.

Kindest wishes to you all.

(This is a really great article and report, by the way; I think that these are latent archaic prejudicial beliefs and attitudes which do surface with political circumstance, but I do also think that we are slowly winning the argument over these decades. A long and damnably hard road ahead still, but great to see so many folks implacably fighting these societal cancers! Good luck to - and heartiest solidarity with - you all!

G,

Refugee Support Worker/Activist.)

4 comments