What happened next?

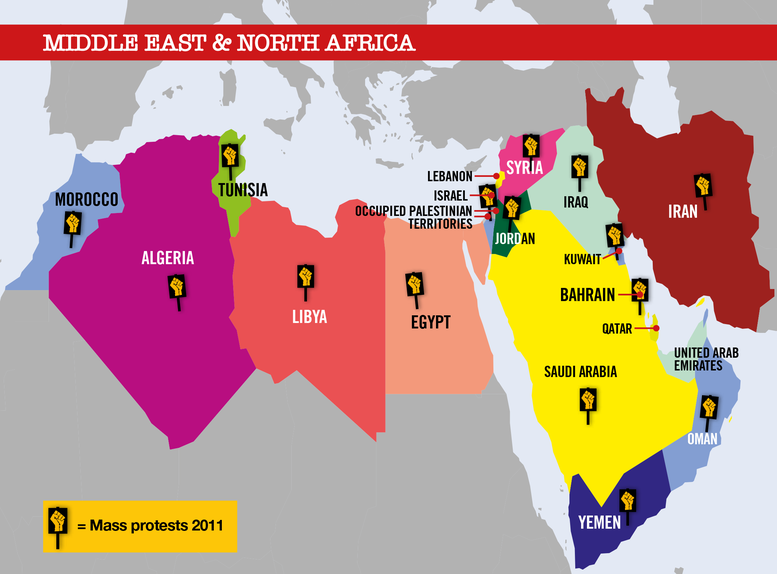

Ten years ago, the Middle East and North Africa was engulfed in an unprecedented outburst of popular protest. It came to be known as The Arab Spring.

Amid demands for an end to mass poverty, corruption, repression, and injustice, some longstanding authoritarian rulers were swept from power.

What happened next?

Here is the story of the Arab Spring in pictures.

-

© Amnesty UK

-

Getty Images

Libya

The February revolution, inspired by events in Tunisia and Egypt, began in Benghazi

in eastern Libya and spread across the country. The opposition established a National Transitional Council (NTC) as a government-in-waiting. The regime cracked down hard and peaceful protests turned into armed rebellion, followed by NATO-led airstrikes that were supposed to protect civilians. Gadaffi was killed in October 2011 and the NTC announced the liberation of Libya. Eight months of war had devastated the country.The new government promised to respect human rights and international humanitarian law, and to amend repressive laws. But it was unable to control the heavily-armed militias formed in the war.

Since 2014, the country is split between competing factions: the internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA), based in Tripoli and the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA), which controls much of eastern Libya. Both sides have foreign support, with Turkey and Qatar backing the GNA, while the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Egypt and Russia back the LNA.

War crimes have been committed by both sides, and the UN arms embargo

is widely ignored. Thousands of people are imprisoned without trial. Torture is widespread in state and militia custody. Across the country, journalists, human rights activists and NGO workers are threatened, abducted and killed by armed groups and militias. Women activists are targeted for gender-based violence and smear campaigns.This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

Libya

The February revolution, inspired by events in Tunisia and Egypt, began in Benghazi

in eastern Libya and spread across the country. The opposition established a National Transitional Council (NTC) as a government-in-waiting. The regime cracked down hard and peaceful protests turned into armed rebellion, followed by NATO-led airstrikes that were supposed to protect civilians. Gadaffi was killed in October 2011 and the NTC announced the liberation of Libya. Eight months of war had devastated the country.The new government promised to respect human rights and international humanitarian law, and to amend repressive laws. But it was unable to control the heavily-armed militias formed in the war.

Since 2014, the country is split between competing factions: the internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA), based in Tripoli and the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA), which controls much of eastern Libya. Both sides have foreign support, with Turkey and Qatar backing the GNA, while the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Egypt and Russia back the LNA.

War crimes have been committed by both sides, and the UN arms embargo

is widely ignored. Thousands of people are imprisoned without trial. Torture is widespread in state and militia custody. Across the country, journalists, human rights activists and NGO workers are threatened, abducted and killed by armed groups and militias. Women activists are targeted for gender-based violence and smear campaigns.This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

-

AFP via Getty Images

Syria

Mass demonstrations were triggered by the mistreatment of young protesters in the southern city of Deraa in March 2011. A new generation of human rights activists emerged, and people’s awareness of

their rights increased dramatically. The regime, alarmed, released dozens of political prisoners and lifted the 40-year state of emergency. But it soon reverted to repression.

Syrian protesters defied extreme violence from the security forces. Thousands were shot dead at peaceful protests, thousands more were arrested and tortured. As the months went by with

President Assad still in power, some in the opposition took up arms. An estimated 10,000 soldiers deserted to join the Free Syria Army. The war began.

Armed conflict brought atrocities on a mass scale and displaced at least half the population by 2016. The government bombed and shelled opposition-held civilian areas, hitting hospitals and medical workers. In government-held areas mass arrests, torture and enforced disappearances continued. Thousands of Syrians have died in custody since 2011. Russian airstrikes in support of the government, starting in 2015, killed hundreds of civilians.

Opposition armed groups also attacked civilian areas, abducted suspected opponents and killed captives.

Today, levels of armed conflict have died down significantly. The regime, with support from Russia and Iran, has regained control over most of the country, although opposition forces, some supported by Turkey, remain in the north.

In government-held territory, any sign of dissent is suppressed. But Syrian human rights defenders are not giving up. Throughout the war they have documented human rights violations and helped civilians of all ages to survive. Some have been forced into exile, where they defend refugee rights and work to bring human rights abusers to justice.

This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

Syria

Mass demonstrations were triggered by the mistreatment of young protesters in the southern city of Deraa in March 2011. A new generation of human rights activists emerged, and people’s awareness of

their rights increased dramatically. The regime, alarmed, released dozens of political prisoners and lifted the 40-year state of emergency. But it soon reverted to repression.

Syrian protesters defied extreme violence from the security forces. Thousands were shot dead at peaceful protests, thousands more were arrested and tortured. As the months went by with

President Assad still in power, some in the opposition took up arms. An estimated 10,000 soldiers deserted to join the Free Syria Army. The war began.

Armed conflict brought atrocities on a mass scale and displaced at least half the population by 2016. The government bombed and shelled opposition-held civilian areas, hitting hospitals and medical workers. In government-held areas mass arrests, torture and enforced disappearances continued. Thousands of Syrians have died in custody since 2011. Russian airstrikes in support of the government, starting in 2015, killed hundreds of civilians.

Opposition armed groups also attacked civilian areas, abducted suspected opponents and killed captives.

Today, levels of armed conflict have died down significantly. The regime, with support from Russia and Iran, has regained control over most of the country, although opposition forces, some supported by Turkey, remain in the north.

In government-held territory, any sign of dissent is suppressed. But Syrian human rights defenders are not giving up. Throughout the war they have documented human rights violations and helped civilians of all ages to survive. Some have been forced into exile, where they defend refugee rights and work to bring human rights abusers to justice.

This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

-

MOHAMMED ABED/AFP/GettyImages

Egypt

Mass protests began in January 2011. As thousands occupied Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the security forces turned to violence. At least 840 protesters were killed and more than 6,000 injured before the president, Hosni Mubarak, stepped down on 11 February.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) took over, to prepare for transfer of power to a civilian government. In 2012, Islamist parties won the parliamentary elections. The Muslim Brotherhood candidate, Mohammed Morsi, was elected president only to be ousted by the military the following year. Former army chief Abdul Fattah al-Sisi won the 2014 presidential election and was re-elected in 2018.

Today, the security forces crack down on all opposition, dissent and criticism. The government has prosecuted satirists, labour activists, journalists and women

who dared to speak out about sexual harassment. Health workers have been arrested for criticising the government’s response to Covid-19. Thousands of people are in prison solely for exercising their rights to freedom of expression or assembly, or on the basis of grossly unfair trials. Covid-19 has aggravated inhumane conditions of detention.

Egypt’s human rights defenders continue their work on a range of issues, from women’s rights and media freedom to environmental rights, criminal justice and the rights of detainees.

This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

Egypt

Mass protests began in January 2011. As thousands occupied Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the security forces turned to violence. At least 840 protesters were killed and more than 6,000 injured before the president, Hosni Mubarak, stepped down on 11 February.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) took over, to prepare for transfer of power to a civilian government. In 2012, Islamist parties won the parliamentary elections. The Muslim Brotherhood candidate, Mohammed Morsi, was elected president only to be ousted by the military the following year. Former army chief Abdul Fattah al-Sisi won the 2014 presidential election and was re-elected in 2018.

Today, the security forces crack down on all opposition, dissent and criticism. The government has prosecuted satirists, labour activists, journalists and women

who dared to speak out about sexual harassment. Health workers have been arrested for criticising the government’s response to Covid-19. Thousands of people are in prison solely for exercising their rights to freedom of expression or assembly, or on the basis of grossly unfair trials. Covid-19 has aggravated inhumane conditions of detention.

Egypt’s human rights defenders continue their work on a range of issues, from women’s rights and media freedom to environmental rights, criminal justice and the rights of detainees.

This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

-

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

Tunisia

In December 2010, in the town of Sidi Bouzid, a young man called Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest at mistreatment by the authorities. His death provoked nationwide demonstrations, which persisted in the face of violence from the security forces. On 14 January 2011 President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia.

A new government was elected. It released prisoners of conscience and permitted more freedom to journalists. Formerly banned political parties were allowed to operate and activist organisations flourished. A new constitution, adopted in 2014, banned torture and asserted the rights to speak freely and to meet. In 2018, a law to eliminate violence against women came into force.

A Truth and Dignity Commission was established to ensure justice for past human rights violations. It investigated more than 62,000 cases of human rights violations going back six decades and referred 173 cases to specialised criminal courts. At least 78 trials began in 2019. Among the accused were former interior ministers, security chiefs and government officials. Some of these trials concern the violent repression of protesters during the revolution – but there are no verdicts so far and victims are still struggling to obtain justice.

Meanwhile, the flowering of basic freedoms has stalled: the authorities have prosecuted people for criticising the security forces and peaceful protesters have been arrested. Tunisians have taken to the streets again, to denounce unemployment, poor living conditions, water shortages, and police violence.

This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

Tunisia

In December 2010, in the town of Sidi Bouzid, a young man called Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest at mistreatment by the authorities. His death provoked nationwide demonstrations, which persisted in the face of violence from the security forces. On 14 January 2011 President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia.

A new government was elected. It released prisoners of conscience and permitted more freedom to journalists. Formerly banned political parties were allowed to operate and activist organisations flourished. A new constitution, adopted in 2014, banned torture and asserted the rights to speak freely and to meet. In 2018, a law to eliminate violence against women came into force.

A Truth and Dignity Commission was established to ensure justice for past human rights violations. It investigated more than 62,000 cases of human rights violations going back six decades and referred 173 cases to specialised criminal courts. At least 78 trials began in 2019. Among the accused were former interior ministers, security chiefs and government officials. Some of these trials concern the violent repression of protesters during the revolution – but there are no verdicts so far and victims are still struggling to obtain justice.

Meanwhile, the flowering of basic freedoms has stalled: the authorities have prosecuted people for criticising the security forces and peaceful protesters have been arrested. Tunisians have taken to the streets again, to denounce unemployment, poor living conditions, water shortages, and police violence.

This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

-

MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP via Getty Images

Yemen

Mass protests erupted in January 2011 when President Ali Abdullah Saleh tried to change the constitution so he could stay in power for life. Hundreds of protesters were killed, but after months of turmoil Saleh resigned, in February 2012. His removal raised hopes of substantial reform.

However, in 2014 an armed group, the Huthis, seized control of the capital, Sana’a, demanding a new government. Saleh’s successor (his former deputy) President Abd Rabba Mansour Hadi, was forced to resign. A Saudi-Arabia led military coalition began air strikes against the Huthis, sent ground troops into Yemen and imposed an air and sea blockade.

The war continues to this day. The coalition bombed civilian infrastructure and carried out indiscriminate attacks. Huthi forces shelled residential areas and fired missiles into Saudi Arabia. All sides obstructed the delivery of aid to civilians. And all resorted to arbitrary detention, enforced disappearances and torture.

Meanwhile, arms flowed to the Saudi- led coalition from the USA, France, Canada and the UK. A court ruling forced the UK government to suspend arms sales to the coalition in 2019, but they resumed in 2020 despite evidence of continuing war crimes. The new US administration suspended arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE in January 2021.

Today, Yemen’s territory is divided between the internationally recognised government of President Hadi, supported by the Saudi-led coalition; the Huthis, backed by Iran; and the Southern Transitional Council, backed by the UAE.

Yemeni human rights defenders document and expose human rights violations by all parties to the conflict, which puts them at great personal risk. Those working for women’s rights are repressed by all sides.

This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

Yemen

Mass protests erupted in January 2011 when President Ali Abdullah Saleh tried to change the constitution so he could stay in power for life. Hundreds of protesters were killed, but after months of turmoil Saleh resigned, in February 2012. His removal raised hopes of substantial reform.

However, in 2014 an armed group, the Huthis, seized control of the capital, Sana’a, demanding a new government. Saleh’s successor (his former deputy) President Abd Rabba Mansour Hadi, was forced to resign. A Saudi-Arabia led military coalition began air strikes against the Huthis, sent ground troops into Yemen and imposed an air and sea blockade.

The war continues to this day. The coalition bombed civilian infrastructure and carried out indiscriminate attacks. Huthi forces shelled residential areas and fired missiles into Saudi Arabia. All sides obstructed the delivery of aid to civilians. And all resorted to arbitrary detention, enforced disappearances and torture.

Meanwhile, arms flowed to the Saudi- led coalition from the USA, France, Canada and the UK. A court ruling forced the UK government to suspend arms sales to the coalition in 2019, but they resumed in 2020 despite evidence of continuing war crimes. The new US administration suspended arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE in January 2021.

Today, Yemen’s territory is divided between the internationally recognised government of President Hadi, supported by the Saudi-led coalition; the Huthis, backed by Iran; and the Southern Transitional Council, backed by the UAE.

Yemeni human rights defenders document and expose human rights violations by all parties to the conflict, which puts them at great personal risk. Those working for women’s rights are repressed by all sides.

This article originally appeared in Issue 208 of Amnesty Magazine. To receive your free copy every quarter featuring all the latest news and opinion about human rights, join Amnesty

What happened next?

Ten years ago, the Middle East and North Africa was engulfed in an unprecedented outburst of popular protest. It came to be known as The Arab Spring.

Amid demands for an end to mass poverty, corruption, repression, and injustice, some longstanding authoritarian rulers were swept from power.

What happened next?

Here is the story of the Arab Spring in pictures.