Northern Ireland election 2017: implications for human rights

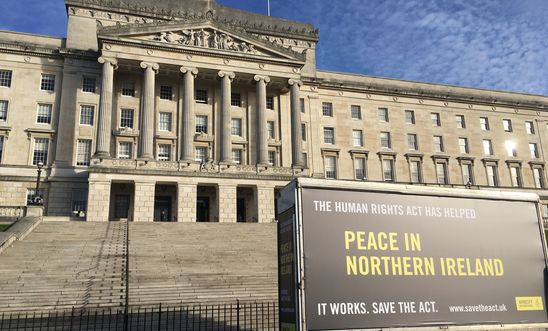

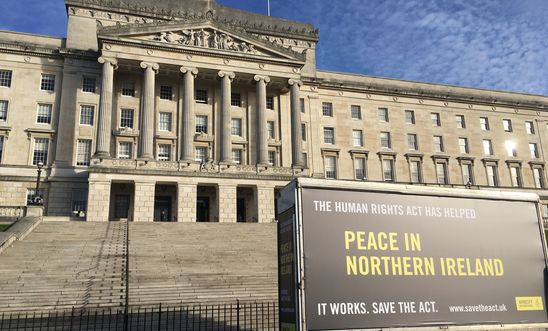

Northern Ireland goes to the polls today (Thursday) to elect new members of the Assembly at Stormont.

If this feels like déjà vu to you, you’d be right. Voters elected a new Assembly less than ten months ago. But it collapsed in acrimony at the start of the year, with Sinn Féin pulling the plug on their power-sharing government with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

On the face of it, the collapse of the government was a response to huge public anger at a financial scandal which could cost the NI budget up to £500 million over the next twenty years. In brief, this is a result of a renewable heating scheme introduced by First Minister (and DUP leader) Arlene Foster when she was Economy Minister and from which she stripped out cost controls present in a near-identical GB scheme. At the very least, this appeared to demonstrate gross incompetence. At its worst, some believe corruption was involved.

But the £500 million overspend in the heating scheme was perhaps simply the straw that broke the camel’s back for a Sinn Féin leadership, who were increasingly being made to look like very junior partners in government by the larger DUP. There was a growing sense among Sinn Féin supporters that whenever the party’s Ministers tried to secure progress on items on their political agenda, they were blocked at every turn by the DUP.

This meant that there was little to no progress on delivering an Irish Language Act, equal marriage and many more issues.

Sinn Féin has vowed there will be “no return to the status quo” after today’s election. That means that rather than forming a fresh government with the DUP (and possibly other parties), Sinn Féin will insist on inter-party negotiations which will likely also include both the UK and Irish governments. This means we are in for a possibly prolonged period of government via civil servants and a return to direct rule from Westminster for at least a period of months.

But what does all this mean for Amnesty International and our human rights agenda in Northern Ireland?

On the downside, for the next while it means we have no NI Executive Ministers to lobby to secure the changes we want to see on issues such as abortion law reform. In the absence of an elected NI government, local civil servants will not have the power to do anything that was not previously legislated for or decided by Ministers before they left office. Equally, unless direct rule looks like it might become permanent (which almost no party wants), UK government ministers will be very reluctant to take far-reaching decisions or pass legislation at Westminster which would otherwise be dealt with at Stormont. Result = political paralysis. Which is not what we, as agents of change, want.

For instance, outside the courts, we are not going to have any way of reforming NI’s restrictive (and human rights violating) abortion laws unless we have an Assembly willing to pass legislation and Ministers willing to introduce policy change. Similarly, while the NI Historical Abuse Inquiry published its report in January, recommendations about the establishment of a redress scheme for victims will go unimplemented without Ministers in place to take decisions.

Rest assured that Amnesty staff and activists will not be sitting on our hands meanwhile. We are already pursuing politicians and government officials to advance these issues and more after the election, whether as part of formal inter-party talks or in parallel while we await a return of government.

On the upside, the post-election period offers a chance to remove some of the blockages which have plagued NI politics for years. This could be a moment of opportunity to secure changes which could deliver positive outcomes for human rights now and in the future.

For instance, there have been countless failed attempts to get political agreement on new mechanisms to ensure human rights-compliant accountability for abuses carried out during Northern Ireland’s thirty-year conflict. This is not just an issue for local parties. The UK government has recently been pushing back on attempts to ensure accountability for killings by members of the British Army in Northern Ireland. Amnesty has been campaigning in earnest on this since 2013 when we published our ‘Time to deal with the past’ report, but we’ve been frustrated by a refusal to agree a comprehensive solution such as we have recommended. This issue will certainly be on the agenda for the post-election talks. If it’s not resolved then, it may never be.

Other human rights issues likely to be directly or indirectly dealt with in such talks will be a Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland, as provided for in the 1998 Good Friday / Belfast Agreement (but still undelivered by the UK government) and equal marriage. On the latter, despite a previous majority vote in the Assembly in favour, the DUP deployed a ‘petition of concern’ to veto the measure and vowed to block it for the next five years.

Here’s the (political) science bit. The petition of concern is a mechanism available in the Assembly, originally designed to protect minority rights (oft-abused in the past) by ensuring that contentious measures have high levels of cross-party support. A petition of concern allows a group of at least 30 MLAs (members of the legislative assembly) to block a decision of the Assembly by requiring a show of “cross-community support”, i.e. the support of a weighted majority (60%) of members voting, including at least 40% of each of the nationalist and unionist designations voting. In practice, it has mostly been deployed by the DUP (the only party which has had at least 30 MLAs of their own) to block a wide variety of measures, such as equal marriage, to which it objects.

Today, for the first time, voters will be electing 90 MLAs to a reduced-size Assembly, rather than the previous 108 members. If the DUP do poorly, as some (though not me) have predicted, they could drop from their current total of 38 MLAs to under 30, thus reducing their ability to use the petition of concern veto power, which will remain at the 30-member threshold. Such an outcome could increase the chances of agreement at the Assembly on a broad range of matters, although nothing would stop the DUP (or others) joining with MLAs from other parties to sign future petitions. However, reform of the petition of concern mechanism may itself be the subject of post-election negotiations.

What happens next? After the votes are counted and the results announced, the new Assembly has to meet within one week of the election. A further two weeks on from that, a new NI Executive must be in place - with first and deputy first ministers (a joint office hitherto shared by the largest parties DUP and Sinn Féin) nominated. I expect Sinn Féin to refuse to nominate, so the Executive will not be able to form.

Consequently, Northern Ireland Secretary of State James Brokenshire MP is supposed to call another election. Instead, he may simply announce a suspension of devolution and a return to direct rule (a drastic step itself) while political talks continue in the months ahead.

Our agenda for human rights remains unchanged. But the political landscape just got a lot more uncertain.

Our blogs are written by Amnesty International staff, volunteers and other interested individuals, to encourage debate around human rights issues. They do not necessarily represent the views of Amnesty International.

0 comments