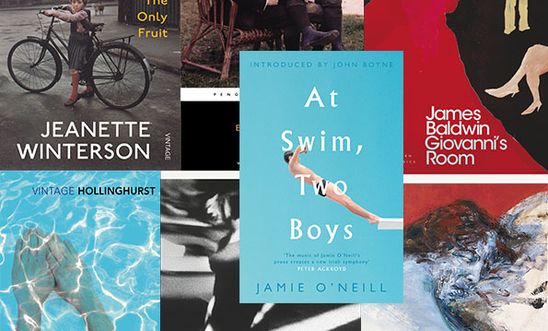

Seven queer books that changed the world

Reviewed by Patrick Cash who is a London-based writer, editor, playwright and spoken word poet, whose work often explores the social challenges of the LGBTQ+ community. He’s collaborated with Amnesty on the Words That Burn project.

Did these books change the world? In terms of empirical evidence the proof is quite scant, I’m afraid, and I can only present here my impassioned reader’s opinions. But they all changed my world to some extent, with their finely tuned, tender depictions of queer lives, and I’d hope they’d allow any reader to feel a greater beauty in life - which, in itself, is another world changed.

Choosing seven queer books out of the magnificent tumults of queer literature was not an easy task. They’re not all happy tales, but they’re very truthful, and I’ve traced a haphazard LGBTQ+ history from 1905 to 2001 should anybody wish to read them in chronological order. Each of these books is a treat in their own right, and each deserves to find new readers to treasure their stories.

A small ask is that you buy them from an independent bookstore like Gay’s The Word in London, or an ethical online bookseller such as Amnesty or Hive, or even borrow them from a library.

De Profundis - Oscar Wilde (1905)

Wilde wrote this long, savagely beautiful epistle to his former lover Lord Alfred Bosie, when imprisoned for ‘gross indecency’ with men. Both cancerously bitter (‘as I sit here in this dark cell in convict clothes, a disgraced and ruined man, I blame myself’) and exquisitely wrought (‘to reject one’s own experiences is to put a lie into the lips of one’s own life’), Wilde exposes Bosie’s callous nature at great length, before ending with a screeching handbrake turn of utter pathos:

‘I have written to you with perfect freedom. You can write to me with the same. What I must know from you is why you have never made any attempt to write to me.’

It is a dark love letter, full of fury; pinioning ennui-filled nineteenth century society’s attitudes towards morality like a butterfly to the board. But ultimately Wilde finds grace, and a self-assertion for himself, from the depths:

‘[I told a great friend that] my life has been full of perverse pleasures and strange passions, and that unless he accepted that fact as a fact about me and realised it to the full, I couldn’t possibly be friends with him any more, or ever be in his company. It was a terrible shock to him, but we are friends, and I have not got his friendship on false pretences.’

Maurice - E. M. Forster (written 1913/14, published 1971)

Forster never published Maurice during his own lifetime, writing the novel in a time when Wilde’s notoriously public downfall was still relatively recent. We follow Maurice Hall to Cambridge, where he falls in love with fellow undergraduate Clive, an aficionado of the Greek writings on same-sex attraction. Yet after university, Clive marries a woman and Maurice begins a downwards spiral, left without an axis to his world: ‘Yes, the heart of his agony would be loneliness… Memories of Clive might pass. But the loneliness remained’.

Forster masterfully depicts the intense isolation of a gay man during the period of illegality, and the mental health issues this may entail: ‘Since coming to Penge he seemed a bundle of voices, not Maurice, and now he could almost hear them quarrelling inside him.’ Yet just as he’s swept the reader down with poor Maurice to the darkest nadirs, Forster introduces an ending that reminds one how life can give as much as it may seem to take.

Although sadly Forster never thought public attitudes were ready for Maurice in his own life, he did live to see the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1968. And after his death in 1970, Maurice rightfully found its way onto bookshelves around the world.

Giovanni’s Room - James Baldwin (1956)

Giovanni’s Room is said to be partly inspired by Baldwin’s own time in Paris escaping American racism, although his protagonist David is not described as a person of colour: ‘my ancestors conquered a continent, pushing across death-laden plains, until they came to an ocean which faced away from Europe into a darker past.’

David runs away from America to the more liberal 1950s Paris, where he’s introduced to an alluring Italian bartender: ‘Giovanni looked at me. And this look made me feel like no one in my life had looked at me directly before.’ An ultimately tragic novel, Baldwin elicits a tender and tantalising flirtation between the two men, before their affair is consummated in the eponymous room:

‘He pulled me against him, putting himself into my arms as though he were giving me himself to carry, and slowly pulled me down with him to that bed. With everything in me screaming No! yet the sum of me sighed Yes.’

Giovanni’s Room appeared just over a decade before Stonewall, heralding the tentative shoots of greater tolerance towards LGBTQ issues. Yet Baldwin himself has said the novel is ‘not so much about homosexuality, it is what happens if you are so afraid that you finally cannot love anybody.’

Last Exit to Brooklyn - Hubert Selby Jr. (1964)

Not necessarily a queer author, but Last Exit to Brooklyn chronicles many aspects of American queer lives, and that, in my book, makes a queer novel. It’s famously remembered now for an obscenity trial when published in the UK, which gave sales a helpful push skywards. But Selby Jr. lived part of his life with the characters he portrays and he attests that his reasons for immortalising them are to highlight ‘the love buried under all this madness, behind the obsession.’

I remember finding it oddly difficult to directly find myself in the homosexual characters, despite the exhilaration and flying sparks of the prose. And I feel, revisiting the novel now, this is because most of the homosexual characters Selby Jr. records are actually male-to-female trans, dressing and living their public lives as women. The opening paragraph to Book II describes Georgette:

‘Georgette was a hip queer… with the wearing of womens clothes complete with padded bra, high heels and wig… and the occasional wearing of a menstrual napkin.’

Don’t come to Last Exit expecting angelic queer characters. These are messy people with asteroid lives, high on benzedrines, and everyday violence is a given. But in recording the truth of life, the book veers to the glorious, and winning its obscenity trial added another paving stone on the path to the legalisation of - and acceptance of - homosexuality.

Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit - Jeanette Winterson (1985)

Allegedly when Jeanette Winterson first published Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit, many confused booksellers stocked it in the Marmalade section. Once rescued from cookbook obscurity, it then found its way onto the newly setup ‘Gay and Lesbian’ shelf, although Winterson, like presumably most of the authors on this list, says ‘all of my books are for anybody and everybody.’

Oranges traces the life of a young girl named Jeanette, whom Winterson freely admits is based on herself, brought up in a Lancastrian Labour mill town by religious zealot parents until the mid-teens realisation of her sexuality. Jeanette’s narration is clever, engaging and very funny, and we come to share both her frustration and her sympathy for her mad and evangelical mother:

‘While some of our church forgave me on the admittedly dubious grounds that I couldn’t help it (they had read Havelock Ellis and knew about inversion), my mother saw it was a wilful act on my part to sell my soul.’

Far richer than your standard coming-of-age novel, Oranges is an intricately layered literary work, covering conversion therapy and betrayal, and punctuated throughout with rewritten fairytales and fables of the Arthurian Grail. The central motif of fruit guides the reader through the book:

‘To eat of the fruit means to leave the garden because the fruit speaks of other things, other longings.’

The Swimming Pool Library - Alan Hollinghurst (1988)

The Swimming Pool Library arrived at a turbulent time for LGBTQ history, just as Section 28 was introduced into UK law and AIDS was decimating a generation.

Hence why Hollinghurst’s debut novel is so startling and vital. It follows 25-year-old William Beckwith, who’s living off his trust fund and sleeping his way through early 1980s London. Described as ‘darkly erotic’ in one of the jacket quotes, which possibly translates to ‘non-heterosexually erotic’, the text revels in a bold, realistically sexual tone: ‘there were more reckless propositioners like the laid-back Ecuadorian Carlos with his foot-long Negroni sausage of a dick.’

But a core engine of the story revolves around an intergenerational connection. Whilst cruising in public toilets, Will saves the life of one Lord Nantwich, who in turn hires Will as his biographer; neatly juxtaposing the elderly man’s history against Will’s pleasure-pulled existence.

Of course, the 80s aren’t remembered now for fearless promiscuity. The novel’s set in the pre-AIDS summer of 1983, and Hollinghurst weaves in foreshadowing references. In a poignant manner, The Swimming Pool Library serves as an elegy to that period between legalisation and a new era.

At Swim, Two Boys - Jamie O’Neill (2001)

Ireland 1915, the world is at war, and two teenage boys agree to swim to the Muglins Rock across Dublin’s Forty Foot Bay. One, Jim, is the pious son of a shopkeeper and the other, Doyle, is the dungman’s monkey. As they practise their swimming, a bond develops and they fall in love. But what may sound like a fairly prosaic plot in paraphrase, is actually a symphony that depicts Ireland establishing itself as a nation against British rule, culminating in the Easter 1916 rebellion:

‘I don’t hate the English and I don’t know do I love the Irish. But I love him. I’m sure of that now. And he’s my country.’

A particular character is named MacMurrough, an Irish aristocrat who has served two years’ hard labour in an English gaol for ‘gross indecency’ with a chauffeur mechanic. The reverential allusion to Wilde is gracefully drawn by O’Neill. MacMurrough is psychologically scarred by his experience, tortured by voices, and always feels he’s younger than his years: ‘just on that threshold before thought or action, his sense of himself was of a burgeoning youth.’

It is in MacMurrough’s coming to mental maturity, through an involvement with the boys’ goal, that he exorcises the voices. Yet the last words he hears may yet speak truth to where modern LGBT culture heads towards in the future, as we forge our own community’s legal maturity:

‘Help these boys build a nation of their own. Ransack the histories for clues to their past. Plunder the literatures for words they can speak… In each such telling, they will falter a step to the light.’

Our blogs are written by Amnesty International staff, volunteers and other interested individuals, to encourage debate around human rights issues. They do not necessarily represent the views of Amnesty International.

0 comments