A short history of human rights and children’s books

By Nicky Parker, Publisher at Amnesty International UK.

This is the second year of the Amnesty CILIP Honour, an extra commendation for two books on the Carnegie and Greenaway Medal shortlists that best uphold, illuminate or celebrate human rights.

The eight decades since the Carnegie Medal was first awarded have encompassed war and devastation, human upheaval and suffering. The same years have also seen great moves to make the world a better place, with a growing international understanding of rights, freedom and equality, and profoundly life-changing human rights laws. These values emerge in contemporary children’s books, which are often beacons of social change. Arguably the most important and least valued of all forms of literature, they influence and shape children’s attitudes to life.

From the Bolshevik Uprising to a Lake District children’s classic

The first Carnegie Medal went to Pigeon Post in 1936 whose author Arthur Ransome is usually portrayed as a conservative writer for and about privileged white British children. But Ransome’s personal history was hardly stereotypical. He had reported on the Bolshevik Revolution, married Trotksy’s secretary, and then abandoned war reporting in favour of children’s books, his protagonists the ‘Swallows’ being inspired by the British-Armenian Altounyan family. His books explore a value later enshrined as Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that ‘education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality’. This is what makes Pigeon Post still relevant 80 years later: his characters are allowed the freedom to explore and take risks, a right now often denied by fearful parents.

From war to literary heroes

Some of the greatest children’s books reflect their authors’ experience of war. In 1937 JRR Tolkien’s classic The Hobbit was nominated for the Carnegie, which in 1956 CS Lewis won for The Last Battle, the last of the Narnia series. Both explore notions of journeys, territorial rights and repression. Both Lewis and Tolkien had suffered the horrors of the Somme. Both would have known of the Geneva Protocol of 1928, a prohibition on chemical and biological warfare, and 1948’s mammoth Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the blueprint for all future human rights legislation, which sought to say ‘never again’ to the horrors of the Holocaust.

The soft lines of Edward Ardizzone, official WW2 artist and winner of the first Kate Greenaway Medal in 1956 with Tim All Alone, illuminate the vulnerability of children in a harsh world, while former WW2 soldier Richard Adams won the Carnegie in 1972 with Watership Down, an allegorical epic with rabbits as heroes in the battle against tyranny and corporate greed. Their flight from poisonous gases echoes the debate that resulted in the signing of the Biological Weapons Convention that same year.

In the early 1960s Amnesty International was founded, the building of the Berlin Wall began, and the South African state forcibly removed 3.5 million people in its inexorable drive to implement total apartheid. Midway through the Vietnam war, Lucy Boston won the Carnegie Medal in 1961 for Strangers at Green Knowe about a young refugee boy and an escaped gorilla. This prescient story explores the human rights to family, sanctuary, home, and freedom from repression.

Inadequate gender parity in children’s books

As the women's movement grew in the 1960s and the Equal Pay Act came into being in 1970, children’s picture books began to show greater gender parity for main characters. By the 1990s there was nearly equal representation of male and female human characters, though male animal characters still outnumbered female by two to one – and not a lot appears to have changed since. The significance of subliminal messaging cannot be underestimated: the stark context is that worldwide one in three women suffers rape or sexual violence.

‘You said I was a warrior. You told me that was my nature, and I shouldn’t argue with it. Father, you were wrong. I fought because I had to. I can’t choose my nature, but I can choose what I do. And I will choose because now I'm free' Lyra Belacqua, Northern Lights

In 1977 Amnesty won the Nobel Peace Prize and the Carnegie was awarded to Turbulent Term of Tyke Tyler with its subversive take on gender assumptions, two years before the arrival of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Violence Against Women (CEDAW). This was a precursor to 1995’s Beijing Declaration, a key global policy document on women’s empowerment – the same year that Philip Pullman’s Carnegie winner Northern Lights put a strong girl character firmly centre stage.

Rites of passage and rights of the child

In 1990 specific protections were given to children by the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the most widely and rapidly ratified human rights treaty in history (to date not ratified by only two countries: Somalia and the United States). It’s interesting to explore fiction for teens through a human rights lens, as the gaining of independence has always been an important theme for young adults. To achieve narrative tension, writers frequently set stories in contexts of multiple violations of human rights, often inspired by real life. Look at Kevin Brookes’ Bunker Diary and Melvyn Burgess’s Junk, both of which won the Carnegie to howls of alarm from those who want children to remain children.

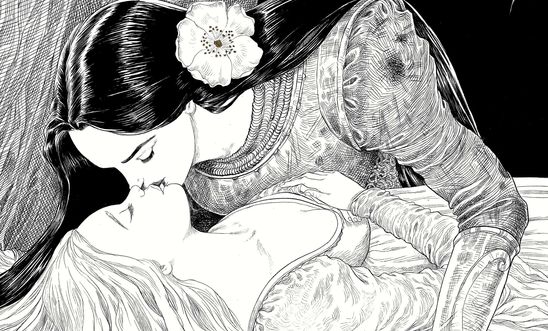

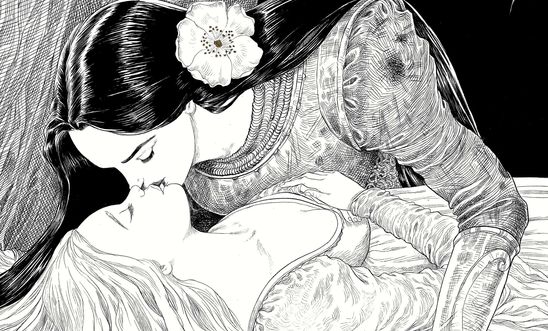

Last year There’s a Bear on My Chair and Lies We Tell Ourselves won the inaugural Amnesty CILIP Honours. Both books explore the right to protest, and turned out to be more timely than any of us realised. Chris Riddell won the Greenaway for The Sleeper and the Spindle, including an image of a same-sex kiss that still has the power to startle us nearly half a century after the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Sarah Crossan won the Carnegie for One, scrutinising the impact of the loss of the right to privacy on the story’s main characters, a few months before the draconian anti-human rights UK Investigatory Powers Act heralded one of the most sweeping surveillance laws in Europe.

If books are building blocks of progress, what next?

Good children’s books are crucial to a well-functioning society, but large swathes of the UK population cannot afford to buy and find it ever-harder to borrow them. Closures of school and public libraries – in defiance of the Public Libraries and Museums Act of 1964 – exacerbate social inequality and restrict intellectual freedoms.

Meanwhile discriminatory and toxic divisions between ‘us and them’ are dominating world politics, young people are experiencing increasing anxiety and the UK government plans to remove us from the European Convention of Human Rights, which will dismantle our access to many precious freedoms.

What can the children’s book world do? For young people to feel valued and to value others, books need to uphold our common humanity, starting with proper representation of voices from all sectors of society. Tokenism is never enough and stories need fully rounded characters. It’s time for publishers and booksellers to challenge entrenched institutional prejudice and discard unproven assumptions that diversity doesn’t sell. We have a collective responsibility to make diversity as normal in children’s literature as it is in life. We are all human after all.

This blog first appeared on the CILIP website.

Our blogs are written by Amnesty International staff, volunteers and other interested individuals, to encourage debate around human rights issues. They do not necessarily represent the views of Amnesty International.

0 comments