Home Office: new plan; same old policies

Yesterday the Home Office published plans for new legislation and other changes to the UK’s immigration system. Ministers are referring to this as a grand new plan. But what is proposed is a pick and mix of many of the most damaging ideas the Home Office has promoted or introduced over the last 20 years or more.

What makes this all so especially dismal, is that these ideas have previously been rejected, done grave harm or both. That harm has been to the people in need of asylum in the UK and to the system that is meant to provide that – including by exacerbating delays and backlogs.

Creating a two-tier asylum system

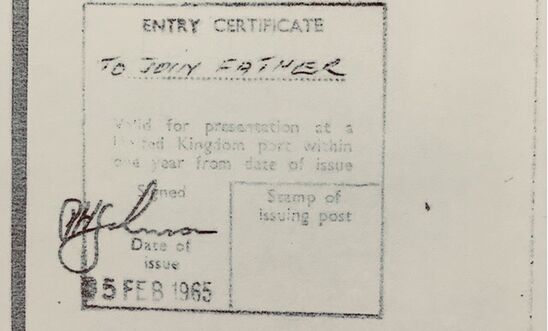

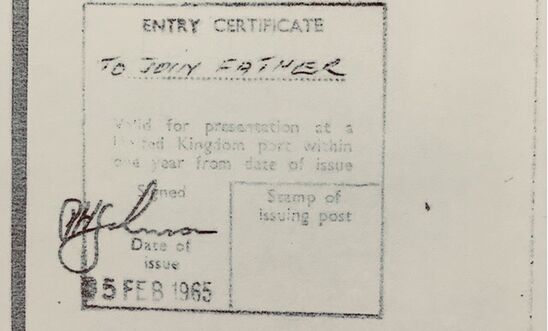

Central to the announcement is the intention to create a two-tier asylum system. This is something the Home Office has repeatedly sought to do since at least the late 1990’s. People who seek asylum by entering the UK without prior permission are to be punished regardless of their need and right to receive protection. This is despite the fact that the great majority of the women, men and children to whom the UK provides asylum have no choice but to do this.

Home Office policy has long been that no claim will be considered if the person has not first reached the UK; and its rules do not authorise anyone to come to this country for that purpose.

A new plan of failed policies

Among the measures now proposed are to withhold or restrict appeal rights against a refusal of asylum if someone has entered the UK without prior permission. This is much like what Michael Howard did all the way back in 1999. It is also proposed to build new asylum reception centres and withhold financial support from people on the basis of how they entered the country. David Blunkett’s first immigration act included each of these measures in 2002.

Ministers say they will introduce what they call a one stop process so that a person discloses every basis for an asylum or other claim ahead of any appeal against refusal. David Blunkett did the same. Also in 2002.

Ministers propose to stop immediately granting permission to stay permanently to people recognised as refugees through the asylum system. But this ended years ago. Charles Clark did it back in August 2005.

Prolonging suffering at greater expense

Doing so has meant that officials must receive and reconsider updated applications from refugees in the UK before granting permission to stay permanently. Not only does this prolong uncertainty for people, undermining their efforts to settle and rebuild their lives, it adds unnecessary work for the Home Office.

Absurdly, Ministers are now proposing to exacerbate the damage by requiring ever more reviews of the decision to grant someone asylum.

And it seems no proposal from this department can be complete without some promise or other to stop people accessing the courts to challenge the legality of expelling them from the UK.

The Home Office has made many changes to law and policy to attempt this over the years – even going so far as to keep secret from people when they are to be removed so they cannot seek advice or ask a judge to intervene.

None of these measures has made the immigration or asylum system any more efficient. Instead, these systems were driven into such a state of collapse that, in 2007, the Home Office established an entirely new section solely directed to trying to clear the huge backlog it had imposed on itself within 5 years.

They did, however, cause much more injustice and forced many people into destitution, homelessness and situations in which they are vulnerable to abuse.

So why are they to be repeated now?

Pointing the finger of blame

There is certainly no rational reason. Not only did these measures do more damage and no good before, the UK’s asylum system has not been receiving any increase in the relatively low number of people coming to this country to claim asylum. Indeed, fewer people claimed asylum in 2020 than did in 2019.

It is true that asylum backlogs are growing. But this is because the Home Office has not been able to make or give effect to asylum decisions during the pandemic in the way it had done previously.

So what is the point?

It is certainly not to reform the culture and practice at the Home Office – something Priti Patel had promised to do last year. Instead, it seems that, as ever, the Home Office has managed to deflect attention from its many and manifest failings by pointing the finger at others.

Smugglers are responsible for the department’s refusal to provide any routes for a person to come to the UK to seek asylum.

Lawyers and courts are responsible for its poor decision-making and excessive use of powers of detention and expulsion.

Refugees and other people who rely upon the immigration and asylum system are not responsible for that system’s inconsistency, complexity and arbitrariness – and the vulnerability and suffering it inflicts upon them.

Sadly, as before, not only is this vilification of people and their rights untrue. It will lead where it has always led – to more injustice, more inefficiency and a repeated cycle of scapegoating from a department that has never wanted or been made to take responsibility for its own failures.