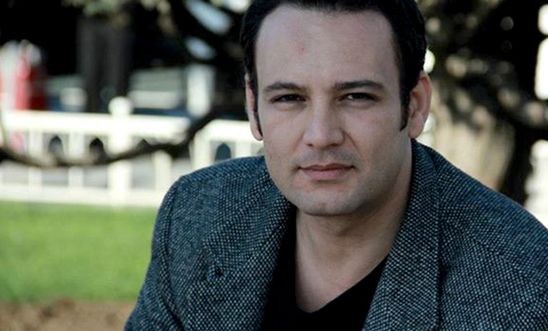

Mansour's fight for justice

Mansour's story

'The first trial for torture in Syria is a truly historic moment'

-Mansour Omari

Tired of being a victim

Sick and tired of being a victim for so many years, with a victim’s perpetual sense of defeat, I sat at my window looking out at a lively street with children hurrying to school.

I was trying to cheer myself up. I was listening to Chris de Burgh’s “Sailing away” while moving my left leg back and forth to ease the pain in the ankle and knee joints. They were damaged when my jailor pushed me blindfolded down the jail stairs, eight years ago.

Since my release in 2013, I’ve been doing what others in my position will often do - “raising awareness”. That is, I’ve been telling my story. And the story of my fellow detainees. Telling it to journalists, to politicians, to academics, to human rights organisations.

Each time I think I’ve said it all a journalist asks something I haven’t previously considered and I’m thrown back into the darkness, three floors underground in a Damascus jail. Back to the darkness and the torture. Then, when the interview’s over, I console myself that at least I’m keeping a promise I made to my fellow prisoners.

But for how much longer? My ability to go on is vanishing. The truth is I don’t want to be a victim anymore. My body and soul are on the verge of collapse. I want to stop travelling from country to country begging the international community to act.

On the other hand, I can’t stop. It’s a torment. I feel I’ve been losing for years. I lost my house, my country and my friends. I lost to my jailer, who left his marks on my body forever. I lost to the world’s inaction. I couldn’t save a single detainee from death under torture. Should I keep on deceiving myself that I can bear to keep losing? Should I lie every time someone says to me “hi, how are you?”

When will it end? When will this endless pain end?

And then comes an answer.

The tables are turning

Last year, Germany issued an arrest warrant against General Jamil Hassan, head of Syria’s notorious Air Force Intelligence Directorate.

It was Gen Hassan who supervised my subterranean torture, and the torture and murder of thousands of others. Hassan ordered my arrest because I was working with a human rights organisation - the Syrian Centre for Media and Freedom of Expression - documenting abuse against detainees.

Now, the tables are turned. He is wanted for crimes against humanity. It was a moment I’d waited for a very long time.

One of my first Facebook posts after release, after pressure from the international community and Amnesty International’s relentless campaigning was a photo of a cup of coffee and a simple sentence: “We are coming back to love, with a cup of coffee whether you - Jamil Hassan and your Air Force Intelligence - like it or not”. Reading it now, after all these years, I can see it was a fierce reassertion of my humanity after those months of underground suffering.

The other event that rekindled hope in my battered soul was news of the trial in Germany of “Anwar R”, a former high-ranking official from Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate. Anwar R. is suspected of being complicit in the torture of at least 4,000 people between 2011 and 2012. This torture resulted in the death of 58 people and included cases of sexual violence. The trial will start in Koblenz on 23 April and I will be there to report on proceedings.

This is momentous. Syrian survivors will finally come face to face with one of their tormentors - a truly historic moment. This will be the first time this has happened not just since the uprising against Bashar al-Assad in 2011, but the first time since the Assad's took power 50 years ago, turning Syria into a family fiefdom governed by a torture-and-kill machine.

Steps towards justice

Me and my fellow Syrian survivors have worked extremely hard for this moment. We’ve been documenting Syria’s mass atrocities for years (it’s now probably the most documented mass crime scene in history).

Following years of advocacy & support from the likes of Amnesty International alongside crucial and groundbreaking work from Syrian human rights groups and organisations like the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights, we’ve now taken a significant step toward justice.

It’s true, I couldn’t save my fellow detainees, and I’ll take this bitter regret to my grave. But I can still do something useful. I can work to prevent this from happening again. And I can work to try to spare future generations of Syrians from suffering the way I did.

Mansour Omari is a Syrian human rights defender. He is currently studying for an LLM in Transitional Justice and Conflict in London.

How Amnesty is helping

Since the uprising in 2011, tens of thousands of people have been forcibly disappeared, tortured and executed in Syria. Victims and families are still demanding justice - and they’re not going to stop. Nor should they, because nine years on, war crimes, crimes against humanity and other serious abuses continue in the country. These crimes will not be forgotten and should never be forgiven.

For several years now, Amnesty International UK has been working with a range of Syrian human rights organisations to help them hold torturers and war criminals to account and bring them to justice. We’re focused on those Syrian groups working on documentation, strategic litigation and victim support, such as the Syrian Centre for Media.

Victims and their families have the right to truth, reparations and justice. We will do everything we can to ensure this happens. We plan to continue our work in Turkey, Lebanon, Germany, France and elsewhere training and equipping Syrian human rights defenders on the frontline of this campaign for justice.

All power to Mansour and his colleagues who are taking the fight to their tormentors.

Kristyan Benedict, Amnesty International UK’s Crisis Manager - @KreaseChan