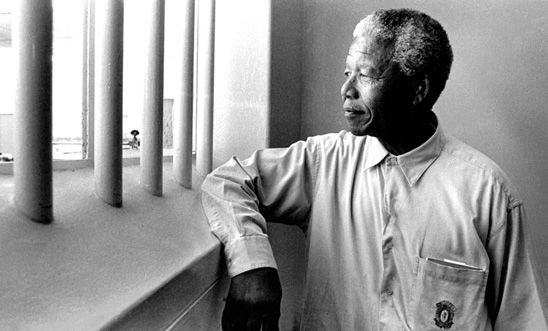

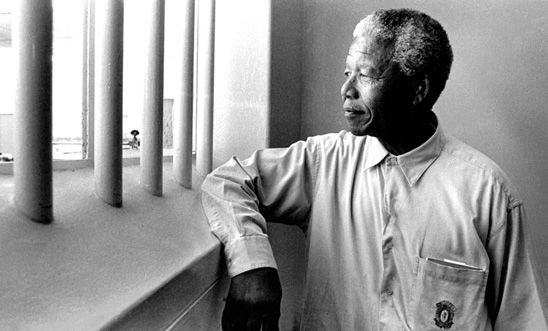

Nelson Mandela and Amnesty International

When we were founded in 1961 our sole purpose was to work to free prisoners of conscience – those unfairly jailed for peacefully speaking out and criticising the authorities.

In 1962, Nelson Mandela was arrested and charged with inciting workers to strike, and travelling without valid documents. One of our founders, lawyer Sir Louis Blom-Cooper, attended the trial as an official observer and when Mandela was sentenced to five years in jail, he was adopted as a prisoner of conscience.

The Rivonia Trial

While in prison, Mandela faced new charges alongside eight others, which included sabotage and armed struggle against the apartheid government.

The new trial saw all nine, including Mandela, convicted in 1964, and the high level of international attention helped save them from the death penalty. But for Amnesty, our dilemma was one around a core principle - that prisoners of conscience are those who do not use or advocate violence. Would Amnesty continue to declare Nelson Mandela a Prisoner of Conscience?

Deeply difficult decision

Our entire global membership was involved in the debate on how we should proceed. In the end we took the decision to no longer consider Mandela a prisoner of conscience. It was a deeply difficult decision to make. Many members were very distressed by his sentence, but also fundamentally felt that we could not been seen to condone violence.

This decision meant that our membership could not campaign for his automatic release as a non-violent prisoner of conscience.

Commenting on the decision our Secretary-General at the time, Peter Benenson said:

‘We recognize, with great sympathy, that where a Government has shown itself contemptuous of the Rule of Law and impervious to peaceful persuasion, that those to whom it has denied full human rights as set out in the United Nations Declaration, may feel or find themselves forced into a position in which the only road to freedom is violence. Such people, though they cannot qualify for adoption as Prisoners of Conscience within the definition of Amnesty International, can be, and often are, our active concern on humanitarian grounds.’

Continued campaigning

Although we were not able to campaign for the automatic release of Mandela, we did make representation to the authorities in South Africa around the fairness of his trial and his prison conditions, and over the years continued to campaign for many others subjected to unfair trials and torture by the South African apartheid regime.

If Nelson Mandela’s case was to arise today, we would call for him to be released on the grounds that he had not been given a fair trial – an area we have worked on since 1964. Unjust systems cannot deliver just verdicts or sentences, and the apartheid system founded on racism did not give Nelson Mandela a fair trial, nor could it have done.

Ambassador of Conscience

Nelson Mandela acknowledged that we made our decision in good faith and thanked us for our work on behalf of thousands of other South African prisoners and detainees.

‘Like Amnesty International, I have been struggling for justice and human rights, for long years. I have retired from public life now. But as long as injustice and inequality persist in our world, none of us can truly rest. We must become stronger still.’

Nelson Mandela, on being presented the Ambassador of Conscience Award in 2006