Online abuse of women is widespread in the UK with one in five women having suffered online abuse or harassment, our latest research has discovered.

Almost half of women said the abuse or harassment they received was sexist or misogynistic, with a worrying 27% saying it threatened sexual or physical assault.

Online abuse of women has offline consequences

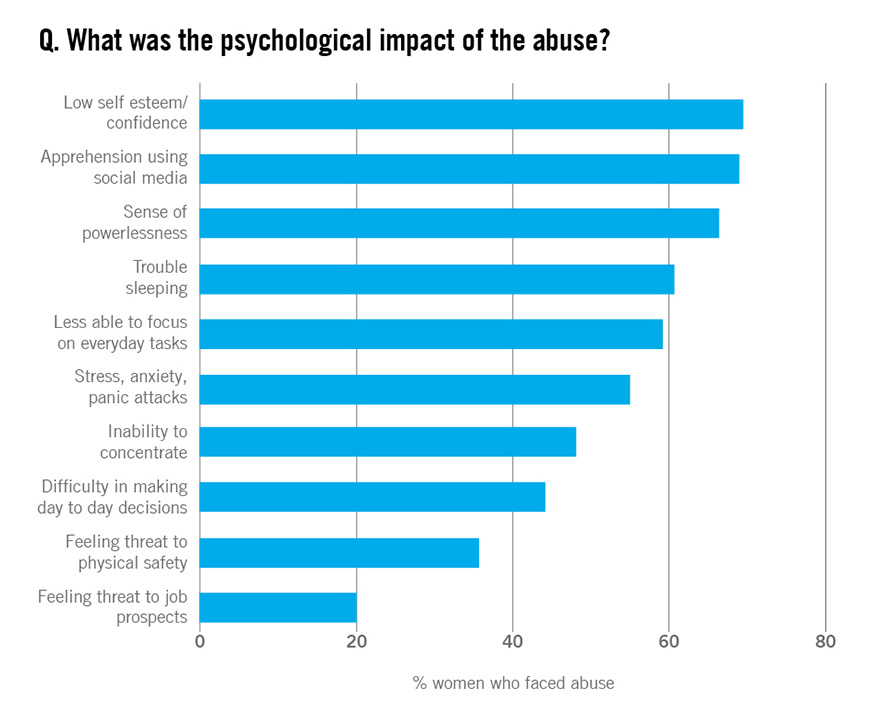

Women are suffering offline consequences of this abuse with 55% saying that they experienced anxiety, stress or panic attacks as a result. Many faced other psychological consequences, such as loss of self-esteem and a sense of powerlessness in their ability to respond to the abuse.

Young women are especially affected, with one in three polled saying that they have experienced online abuse.

Laura Bates, founder of the Everyday Sexism Project – an online initiative to catalogue instances of sexism – is trying to combat this worrying development. She said:

“We are seeing young women and teenage girls experiencing online harassment as a normal part of their existence online. Girls who dare to express opinions about politics or current events often experience a very swift, misogynistic backlash. This might be rape threats or comments telling them to get back in the kitchen.

“It’s an invisible issue right now, but it might be having a major impact on the future political participation of those girls and young women. We won’t necessarily see the outcome of that before it’s too late.”

Laura experiences online abuse every day for speaking out for women’s rights. She continued:

“When I stop and think about it, it’s actually very sad. It’s become a normal state feeling permanently under siege. You think about these things all the time until it becomes a normal kind of living situation, where you’re constantly looking over your shoulder and worried about the safety risks.”

This was reflected in our research, with over a third of women saying they felt their physical safety was at threat due to the abuse they received.

Poorly supported

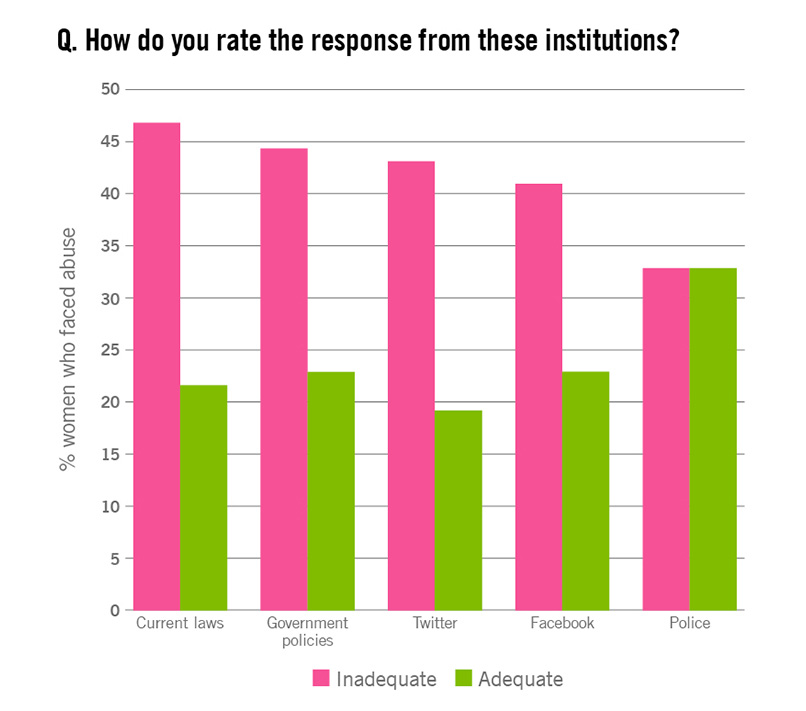

Most of the women we polled rated the response to online abuse or harassment from the relevant institutions to be inadequate (see graph below).

Only 23% of Facebook and 19% of Twitter users rated the platforms’ response in addressing online abuse or harassment as adequate, versus 41% and 43% who considered it inadequate.

Seyi Akiwowo, councillor for the Forest Gate North Ward in London, received a wave of online abuse after a video of her speaking at the European Parliament went viral.

She reported the instances of the abuse to Twitter – sometimes as many as 70 in one day – but until her case became mainstream news, no action was taken. She said:

“I never heard, ‘we have seen that you have reached out to us…’ they only responded to some of the reports I made. But I had to send reports like three or four times. To the point where they were now trolling my colleagues.

“They only started suspending those accounts, pulling those accounts and deleting those tweets after the London Tonight show. So if not for London Tonight, I am not sure what would have happened.”

Online abuse is a human rights issue

Online violence and abuse of women is part of a wider problem of discrimination and violence against women offline.

As we have seen from this poll, online abuse can have just as severe consequences as abuse experienced offline, with worrying psychological consequences. It may also affect women’s human rights to safety, freedom of expression and participation in public life.

These results also show that women do not feel supported enough by social media companies, government or the police. All these institutions must do more to prevent, and respond to, all acts of violence and abuse against women online. They must also ensure that women are able to use social media platforms freely and without fear.

How we got this data

The poll was conducted by Ipsos MORI in June 2017 using an online quota survey of 500 women aged 18-55 in eight countries (UK, USA, New Zealand, Spain, Italy, Poland, Sweden and Denmark) via the Ipsos Online Panel system.

To ensure a representative spread of data, quotas were set on the age, region and working status of the women surveyed. Data were weighted using a RIM weighting method to correct for potential biases in the sample.

To supplement the data we drew on expert evidence and also conducted personal interviews with women who have experienced online harassment and abuse.