Press releases

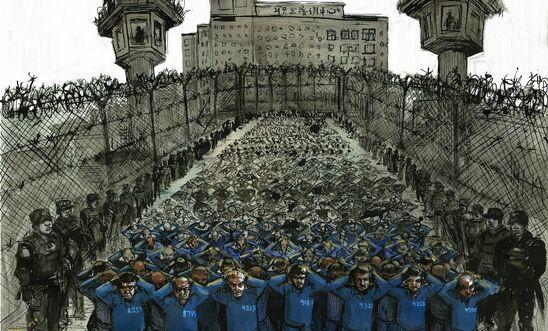

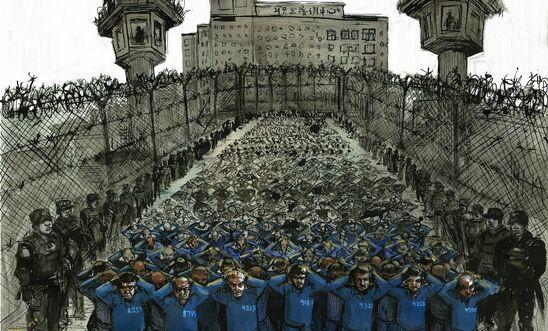

China: UN Human Rights Council risks being 'complicit in cover-up' of Xinjiang atrocities

Council must mandate an independent international mechanism to investigate crimes

People who recently fled Xinjiang tell Amnesty of ongoing abuse and disappearance

Free Xinjiang Detainees campaign now profiles 126 women and men

‘The Council must issue a response commensurate with the scale and gravity of the violations’ - Agnès Callamard

The UN Human Rights Council must end its years of inaction and establish an independent international mechanism to investigate crimes under international law in Xinjiang, Amnesty International said today.

The Council session, which began on 12 September, is the first since the UN High Commissioner’s recent report on atrocities in Xinjiang. The long-overdue assessment corroborates extensive evidence of serious human rights violations against Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minority communities, documented by Amnesty and other human rights organisations.

People who recently fled Xinjiang and family members of detainees continue to report that people in the region are still being persecuted and arbitrarily detained purely on the basis of their religion and ethnicity.

Agnès Callamard, Amnesty International’s Secretary General, said:

“The Human Rights Council has consistently failed to protect the human rights of millions of Muslims in Xinjiang who have suffered countless atrocities over the past five years. Many member states of the Council used the former High Commissioner’s long-standing silence to justify their own.

“The Council must issue a response commensurate with the scale and gravity of the violations.

“If Council members fail to act now, they will become complicit in the Chinese government’s cover-up.

“It would send a dangerous message to Chinese authorities that member states can be bullied into ignoring credible evidence of serious human rights violations, and that powerful states are beyond effective scrutiny.”

Amnesty is calling on Council members to take concrete steps towards halting the Chinese authorities’ abuses and ensure accountability. The Council must table a resolution during this session and mandate an independent international mechanism to investigate crimes under international law and other serious human rights violations in Xinjiang, with a view to ensuring accountability, including through the identification of suspected perpetrators.

Member states must also immediately and unequivocally demand that the Chinese government release all those arbitrarily detained in internment camps, prisons or other facilities, as well as commit to returning no one to China who is at risk of persecution or other serious human rights violations.

China’s cover-up in Xinjiang

The Chinese authorities have attempted to block investigations by the High Commissioner for Human Rights and others, and have pressured UN member states to minimise or ignore the evidence available. As a result, UN investigators were not permitted to go to Xinjiang and the scope of the High Commissioner’s investigation was limited.

By speaking to UN or other investigators or journalists, people living in or with family ties to Xinjiang have risked detention, arrest, imprisonment, torture and enforced disappearance, for themselves and their family members.

People fleeing Xinjiang

Between January and June this year, Amnesty researchers visited Central Asia and Turkey to interview people who had recently fled Xinjiang as well as family members of those arbitrarily detained.

Overwhelmingly, those who fled recently were too terrified to speak openly about their experiences - fearing retaliation against family members still in Xinjiang.

However, six people who fled Xinjiang between late 2020 and late 2021 agreed to speak to Amnesty on the condition of anonymity. They described a life of relentless oppression in Xinjiang, stemming from Chinese policies to severely restrict the freedoms of predominantly Muslim ethnic groups. These include grave violations of the rights to liberty and security; restrictions on privacy and freedom of movement; suppression of freedom of expression including that of thought, conscience, religion, and belief; restrictions on the ability to take part in cultural life; inequality and discrimination as well as forced labour.

An ethnic Kazakh man who left Xinjiang in early 2021 told Amnesty how people in his town were still unable to practice their religion.

He said:

“The religious restrictions remain [in 2021]… There were five mosques [in my town] – four were destroyed… The remaining one is guarded and monitored… Nobody goes! … Maybe [people pray] in the dark of night with the window closed, in silence.”

Amnesty also interviewed the mother of Erbolat Mukametkali, an ethnic Kazakh man. Erbolat was arrested in March 2017, spending a year in internment camps, and was then given a 17-year prison sentence. Erbolat’s mother believes he was arrested solely because of his religious practices.

She said:

“I miss my son… I’m old, my dream is to die when my son is with me.”

Amnesty also interviewed a male relative of Berzat Bolatkhanm, an ethnic Kazakh, who was arrested in April 2017 after being accused of being a “state traitor”. His relative believes that Berzat was arrested because of his ethnicity and because he was planning to move to Kazakhstan. After a year in an internment camp, Berzat was given a 17-year prison sentence.

Berzat’s relative told Amnesty:

“He was just doing his job. He was a farmer. Suddenly, because he wanted to move to Kazakhstan… police arrested him… He is not an extremist, not a terrorist.”

Among Amnesty’s more recent interviewees was a woman who now lives in Turkey. Her sister Muherrem Muhammed Tursun, a primary school teacher, disappeared in August last year after posting a video on her WeChat profile about her family celebrating Eid. Her family believes she was detained due to her Uyghur ethnicity and because her son went to Turkey to study religion before going back to Urumqi to study dentistry. He was taken away in early 2017 while Muherrem’s mother, Tajinisa Emin, was taken to an internment camp in 2020. When their relatives in Turkey tried to find out more details, a relative still in the region simply replied: “don’t ask questions, they are gone.”

These individuals are only a fraction of the likely hundreds of thousands of people arbitrarily detained in Xinjiang, Amnesty has profiled 126 in its Free Xinjiang Detainees campaign. The Council’s failure to act now would be tantamount to abandoning the survivors and families of victims who have jeopardised their safety by speaking out.