Press releases

Iran: leaked letters reveal coronavirus prisons crisis despite 'no deaths' claim

Leaked official documents obtained by Amnesty International reveal that the Iranian Government has ignored repeated pleas by senior prison officials for additional resources to control the spread of COVID-19 in the country’s prison system.

Amnesty has seen copies of four letters signed by officials at Iran’s Prisons Organisation - which operates under the supervision of the judiciary - to the Ministry of Health, raising alarm over serious shortages of protective equipment, disinfectant products and essential medical devices. The Ministry of Health failed to respond, and Iran’s prisons remain catastrophically ill-equipped for dealing with outbreaks.

The details in the letters stand in stark contrast to public statements by the Prisons Organisation’s former head - and current advisor to the head of the judiciary - Asghar Jahangir, who has lauded Iran’s “exemplary” initiatives to protect prisoners from the pandemic.

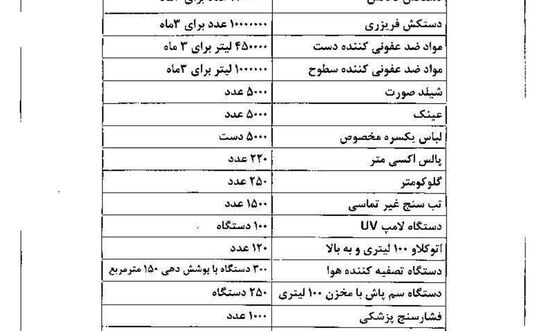

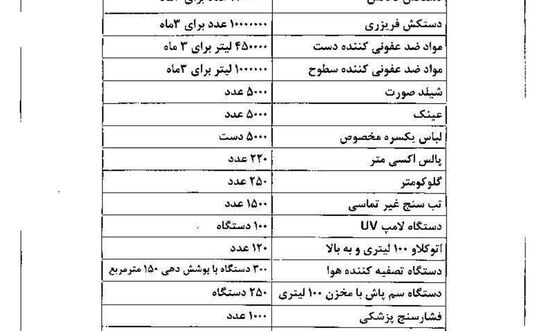

The head of the healthcare office of the Prisons Organisation first submitted a letter to Iran’s Ministry of Health on 29 February. Four follow-up letters were submitted on 25 March, 12 May, 14 June and 5 July. The 25 March letter requested a three-month supply of disinfectant products and protective equipment - including “5,400,000 masks, 10,000 N95 masks, 3,600,000 latex gloves, 10,000,000 plastic gloves, 450,000 litres of hand sanitisers and 1,000,000 litres of surface disinfectant, 5,000 face shields, 5,000 protective goggles, 5,000 protective gowns, 300 air ventilation systems and 250 de-infestation machines”. The letter also highlighted an urgent need for funding to purchase hundreds of essential medical devices, including blood pressure and blood glucose monitors, thermometers, pulse oximeters, stethoscopes and defibrillators.

While the letter does not clarify how many prisons these items and devices were intended for, the figures raise concerns about very serious shortages in prisons across the country.

The letter warned that “security hazards” and “irreparable harm” will result from inaction, particularly considering that Iran’s prisons are “populated with individuals who have pre-existing medical problems, use drugs, and/or suffer from malnutrition, anaemia, and infectious diseases such as HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis”. It also notes that Iran’s prisons house “older [people], pregnant women, nursing mothers and their infants who suffer from a weak immune system due to their low socio-economic status and hygiene”.

Subsequent letters repeat these requests and note the absence of a Government response.

Diana Eltahawy, Amnesty International’s Middle East Deputy Director, said:

“These official letters provide damning evidence of the government’s appalling failure to protect prisoners.

“Overcrowding, poor ventilation, lack of basic sanitation and medical equipment, and deliberate neglect of prisoners’ health problems, are making Iranian prisons a perfect breeding ground for COVID-19.

“The Iranian authorities must stop denying the health crisis in Iran’s prisons and take urgent steps to protect prisoners’ health and lives.

“We once again call on the Iranian authorities to urgently address overcrowding in prisons, including by immediately and unconditionally releasing all those detained for the peaceful exercise of their rights.”

At least 20 reported deaths

On 6 April, Asghar Jahangir said in a media interview that prisoners enjoy “better standards of healthcare and sanitation than they would in society”, claiming that medical teams were stationed in prisons to monitor the health of inmates daily, with prisoners who showed symptoms immediately tested and transferred to hospitals outside the prison if necessary. Jahangir claimed there had not been a single case of a COVID-19 related death in prisons.

However, the documents obtained by Amnesty - together with the information received from prisoners, their families and independent human rights activists - paint a far grimmer picture.

Amnesty has received distressing reports of prisoners displaying COVID-19 symptoms being neglected for days, even when they have pre-existing heart and lung problems, diabetes or asthma. When their conditions worsen, many are merely quarantined in a separate section in the prison or placed in solitary confinement, without access to adequate healthcare. At least one prisoner who tested positive, Zeynab Jalalian, has been forcibly disappeared since 25 June. She had been on hunger strike for six days over the authorities’ refusal to transfer her to a medical centre outside Shahr-e Rey prison (also known as Gharchak) for COVID-19 related treatment.

Sometimes, as seen most recently in the case of ailing human rights defender and prisoner of conscience Narges Mohammadi, the authorities have refused to inform prisoners of the results of their COVID-19 tests.

Independent human rights groups with contacts inside prisons have reported more than 20 cases of suspected coronavirus-related deaths in prisons, including from Ghezel Hesar prison (2) in Alborz province; Greater Tehran Central Penitentiary (6) and Shahr-e Rey prison (2) in Tehran Province; Urumieh prison (8) in West Azerbaijan province; Kamyaran (1) and Saqez (1) prisons in Kurdistan province; and Sepidar prison (1) in Khuzestan province.

A request by WHO officials to visit Evin prison in Tehran was rejected in March, according to media reports.

Bulging jails despite prisoner releases

In late February and late May, the Iranian authorities announced they had temporarily released around 128,000 prisoners on furlough and pardoned another 10,000 in response to the pandemic. On 15 July, as COVID-19 cases spiked again, a spokesperson announced that the head of the judiciary had issued new guidelines to facilitate a second round of releases.

However, hundreds of prisoners of conscience have been excluded from these welcome measures - including human rights defenders, foreign and dual nationals, environmentalists, individuals detained due to their religious beliefs, and people arbitrarily detained in connection with the November protests. The authorities have also continued to detain unjustly convicted protesters, dissidents, minority rights activists and human rights defenders. Some prisoners of conscience who had been granted leave in March have also been called back to prison.

According to recent official statements, as of 13 June Iran’s prison population was approximately 211,000, two and half times more than the official 85,000 capacity. In July of last year, Iran’s prison population was 240,000, according to officials.

Filthy conditions, denial of medical care and prison protests

Widely-documented concerns in Iran’s prisons include: lack of proper ventilation, filthy and insufficient bathroom facilities, lack of adequate facilities for prisoners to maintain personal hygiene, widespread insect infestations, insufficient potable water and poor-quality food, and a severe shortage of beds - meaning many prisoners have to sleep on the floor. Since the outbreak of the virus, some prisoners have also complained about the authorities’ improper use of bleach to disinfect surfaces, exacerbating poor air quality and leading to severe coughs, chest tightness and asthma attacks.

Amnesty has previously documented the Iranian authorities’ deliberate denial of healthcare to prisoners of conscience and others held in relation to politically-motivated cases, putting their lives at grave risk. In some cases, the denial of healthcare was clearly intended to punish, intimidate or humiliate prisoners, or obtain forced “confessions”.

Since March, the appalling conditions in Iran’s prisons and concerns over the spread of the coronavirus have led to hunger strikes, protests, rioting and escape attempts at jails across the country. The authorities have generally responded to protests violently, using excessive or unnecessary force, and in some cases firing tear gas, metal pellets and live ammunition, resulting in deaths and injuries.