What is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

The UDHR is an enduring commitment to prevent the bleakest moments in history from happening again.

'The UDHR is living proof that a global vision for human rights is possible, doable, workable.'

Agnes Callamard's keynote address to Amnesty International’s 2023 Global Assembly

When was the UDHR created?

The UDHR emerged from the ashes of war and the horrors of the Holocaust. The traumatic events of the Second World War brought home that human rights are not always universally respected. The extermination of almost 17 million people during the Holocaust, including 6 million Jews, horrified the entire world. After the war, governments worldwide made a concerted effort to foster international peace and prevent conflict. This resulted in the establishment of the United Nations in June 1945.

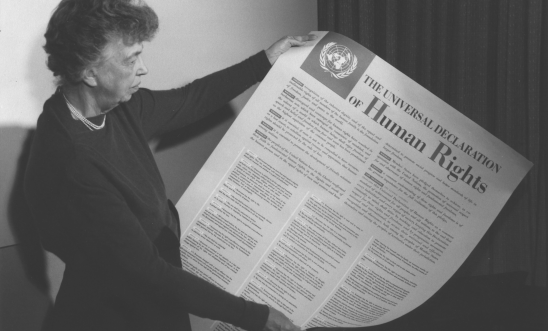

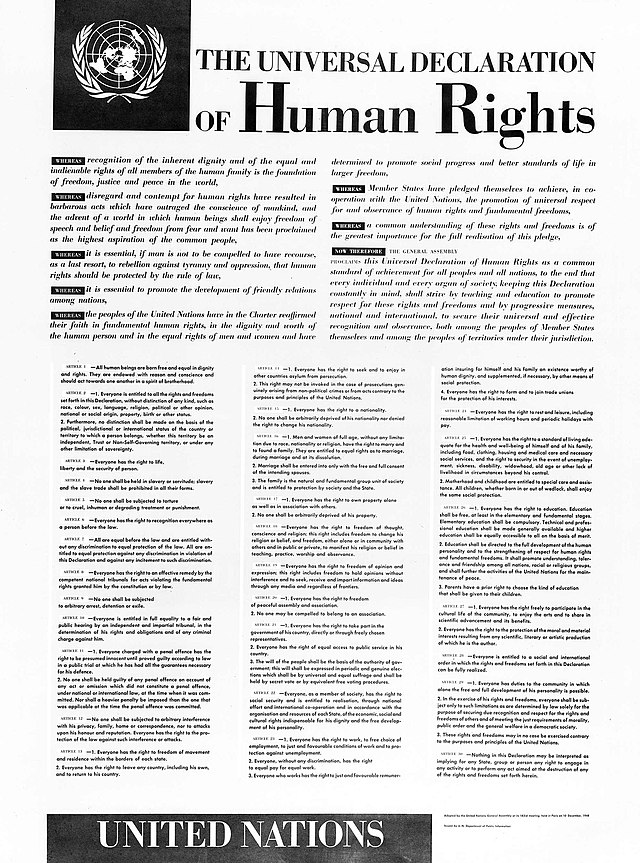

On 10 December 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations announced the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) - 30 rights and freedoms that belong to all of us. Seven decades on and the rights they included continue to form the basis for all international human rights law.

On 10 December 2023 we are celebrating the UDHR's 75th anniversary, reflecting on the enduring power of these principles to inspire positive change worldwide.

Who created the UDHR?

In 1948, representatives from the 50 member states of the United Nations came together, with Eleanor Roosevelt (First Lady of the United States 1933-1945) chairing the Human Rights Commission, to devise a list of all the human rights that everybody across the world should enjoy. Her famous 1958 speech captures why human rights are for every one of us, in all parts of our daily lives:

'Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home - so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighbourhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.'

Eleanor Roosevelt, 1958, during a speech at the United Nations called ‘Where Do Human Rights Begin?’

Hansa Mehta was the delegate of India, and the only other female delegate to the Commission. She is credited with changing the phrase "All men are born free and equal" to "All human beings are born free and equal" in the Declaration.

Various delegations contributed to the writing of the Declaration, ensuring the UDHR promised human rights for all, without distinction. The Egyptian delegate confirmed the universality principle, while women delegates from India, Brazil and the Dominican Republic disrupted the proceedings to ensure the gender equality. Other delegations disrupted the attempts by the Belgium, France and UK delegations to weaken provisions against racial discrimination.

'That’s why we celebrate the UDHR, not because of who wrote it into history, but because of those who used it to disrupt history.'

Agnes Callamard's keynote address to Amnesty International’s 2023 Global Assembly

Why is the UDHR important?

The UDHR marked an important shift by daring to say that all human beings are free and equal, regardless of colour, creed or religion. For the first time, a global agreement put human beings, not power politics, at the heart of its agenda. Communities, movements and nations across the world took the UDHR disruptive power to drive forward liberation struggles and demands for equality.

Although it is not legally binding, the protection of the rights and freedoms set out in the Declaration has been incorporated into many national constitutions and domestic legal frameworks. All states have a duty, regardless of their political, economic and cultural systems, to promote and protect all human rights for everyone without discrimination.

The UDHR has three principles: universality, indivisibility and interdependency

- Universal: this means it it applies to all people, in all countries around the world. There can be no distinction of any kind: including race, colour, sex, sexual orientation or gender identity, language, religion, political or any other opinion, national or social origin, of birth or any other situation

- Indivisible: this means that tking away one right has a negative impact on all the other rights

- Interdependent: this means that all of the 30 articles in the Declaration are equally important. Nobody can decide that some are more important than others.

A summary of the 30 articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The 30 rights and freedoms set out in the UDHR include the right to asylum, the right to freedom from torture, the right to free speech and the right to education. It includes civil and political rights, like the right to life, liberty, free speech and privacy. It also includes economic, social and cultural rights, like the right to social security, health and education.

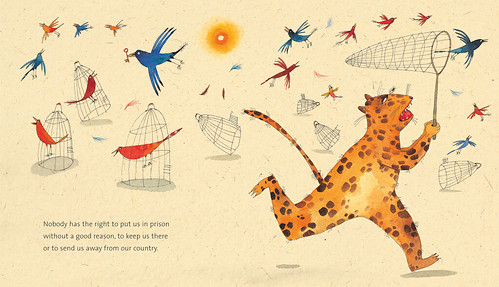

Buy this illustrated collection for children

What are the UDHR articles?

Article 1: We are all born free. We all have our own thoughts and ideas and we should all be treated the same way.

Article 2: The rights in the UDHR belong to everyone, no matter who we are, where we’re from, or whatever we believe.

Article 3: We all have the right to life, and to live in freedom and safety.

Article 4: No one should be held as a slave, and no one has the right to treat anyone else as their slave.

Article 5: No one has the right to inflict torture, or to subject anyone else to cruel or inhuman treatment.

Article 6: We should all have the same level of legal protection whoever we are, and wherever in the world we are.

Article 7: The law is the same for everyone, and must treat us all equally.

Article 8: We should all have the right to legal support if we are treated unfairly.

Article 9: Nobody should be arrested, put in prison, or sent away from our country unless there is good reason to do so.

Article 10: Everyone accused of a crime has the right to a fair and public trial, and those that try us should be independent and not influenced by others.

Article 11: Everyone accused of a crime has the right to be considered innocent until they have fairly been proven to be guilty.

Article 12: Nobody has the right to enter our home, open our mail, or intrude on our families without good reason. We also have the right to be protected if someone tries to unfairly damage our reputation.

Article 13: We all have the right to move freely within our country, and to visit and leave other countries when we wish.

Article 14: If we are at risk of harm we have the right to go to another country to seek protection.

Article 15: We all have the right to be a citizen of a country and nobody should prevent us, without good reason, from being a citizen of another country if we wish.

Article 16: We should have the right to marry and have a family as soon as we’re legally old enough. Our ethnicity, nationality and religion should not stop us from being able to do this. Men and women have the same rights when they are married and also when they’re separated. We should never be forced to marry. The government has a responsibility to protect us and our family.

Article 17: Everyone has the right to own property, and no one has the right to take this away from us without a fair reason.

Article 18: Everyone has the freedom to think or believe what they want, including the right to religious belief. We have the right to change our beliefs or religion at any time, and the right to publicly or privately practise our chosen religion, alone or with others.

Article 19: Everyone has the right to their own opinions, and to be able to express them freely. We should have the right to share our ideas with who we want, and in whichever way we choose.

Article 20: We should all have the right to form groups and organise peaceful meetings. Nobody should be forced to belong to a group if they don’t want to.

Article 21: We all have the right to take part in our country’s political affairs either by freely choosing politicians to represent us, or by belonging to the government ourselves. Governments should be voted for by the public on a regular basis, and every person’s individual vote should be secret. Every individual vote should be worth the same.

Article 22: The society we live in should help every person develop to their best ability through access to work, involvement in cultural activity, and the right to social welfare. Every person in society should have the freedom to develop their personality with the support of the resources available in that country.

Article 23: We all have the right to employment, to be free to choose our work, and to be paid a fair salary that allows us to live and support our family. Everyone who does the same work should have the right to equal pay, without discrimination. We have the right to come together and form trade union groups to defend our interests as workers.

Article 24: Everyone has the right to rest and leisure time. There should be limits on working hours, and people should be able to take holidays with pay.

Article 25: We all have the right to enough food, clothing, housing and healthcare for ourselves and our families. We should have access to support if we are out of work, ill, elderly, disabled, widowed, or can’t earn a living for reasons outside of our control. An expectant mother and her baby should both receive extra care and support. All children should have the same rights when they are born.

Article 26: Everyone has the right to education. Primary schooling should be free. We should all be able to continue our studies as far as we wish. At school we should be helped to develop our talents, and be taught an understanding and respect for everyone’s human rights. We should also be taught to get on with others whatever their ethnicity, religion, or country they come from. Our parents have the right to choose what kind of school we go to.

Article 27: We all have the right to get involved in our community’s arts, music, literature and sciences, and the benefits they bring. If we are an artist, a musician, a writer or a scientist, our works should be protected and we should be able to benefit from them.

Article 28: We all have the right to live in a peaceful and orderly society so that these rights and freedoms can be protected, and these rights can be enjoyed in all other countries around the world.

Article 29: We have duties to the community we live in that should allow us to develop as fully as possible. The law should guarantee human rights and should allow everyone to enjoy the same mutual respect.

Article 30: No government, group or individual should act in a way that would destroy the rights and freedoms of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.