China: Ethnic Kazakh Artist At Risk Of Torture

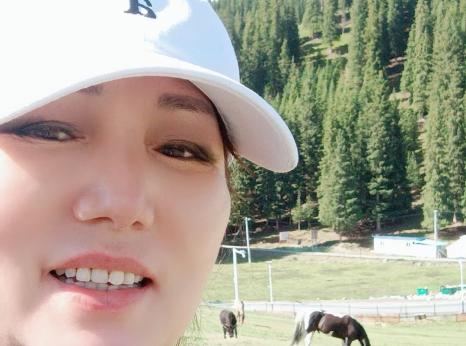

Zhanargul Zhumatai, a 47-year-old ethnic Kazakh woman, resides in Urumqi, Xinjiang, at her mother’s house. From a young age, Zhumatai had a passion for the arts and displayed impressive musical abilities. She aspired to showcase the music and culture of her community to a broader audience. According to her profile in the Xinjiang victims database, Zhumatai arrived in Kazakhstan for the first time in 1999, where she pursued her education at Al-Farabi Kazakh National University. Afterward, she worked as a journalist and established her own arts company. In 2008, she returned to China and dedicated herself to organizing exhibitions and events aimed at preserving Kazakh culture, for which she has received several awards.

In addition to her dedication to preserving Kazakh culture, Zhumatai took it upon herself to advocate for the rights of Kazakh shepherds in Xinjiang. This resulted in multiple instances of harassment by Chinese authorities who were unhappy with her speaking against government appropriation of ethnic Kazakh herding communities' lands. Zhumatai was subsequently taken to Dabancheng Vocational Training Center on 2 March 2018 where she was detained for two years 23 days. During her detention in the camp, she was shackled, handcuffed and subjected to beatings without access to adequate medical care.

Zhumatai, who previously worked as a journalist for the state-run Kazakhstan channel, has the right to reside in Kazakhstan.

Xinjiang is one of the most ethnically diverse regions in China. More than half of the region’s population of 22 million people belong to mostly Turkic and predominantly Muslim ethnic groups, including Uyghurs (around 11.3 million), Kazakhs (around 1.6 million) and other populations whose languages, cultures and ways of life vary distinctly from those of the Han who are the majority in “interior” China.

Since 2017, under the guise of a campaign against “terrorism” and “religious extremism”, the government of China has carried out massive and systematic abuses against Muslims living in Xinjiang. It is estimated that over a million people have been arbitrarily detained in internment camps throughout Xinjiang since 2017.

The Chinese authorities had denied the existence of internment camps until October 2018, when they began describing them as voluntary, free “vocational training” centres. China’s explanation, however, fails to account for the numerous reports of beatings, food deprivation and solitary confinement that have been collected from former detainees.

The report “Like We Were Enemies in a War”: China’s Mass Internment, Torture, and Persecution of Muslims in Xinjiang is the most comprehensive account to date of the crushing repression faced by Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities in Xinjiang. The evidence Amnesty International has gathered provides a factual basis for the conclusion that the Chinese government has committed at least the crimes against humanity of imprisonment, torture, and persecution.

In June 2021 Amnesty launched the international campaign Free Xinjiang Detainees highlighting the stories of 126 men, women, and children reportedly missing or subjected to enforced disappearance or believed to be arbitrarily detained in internment camps or prisons in Xinjiang. They are representative of the over one million people estimated to have been missing, enforced disappeared, and arbitrarily detained in internment camps and prisons throughout Xinjiang since 2017.

In August 2022, the OHCHR released a long-awaited report reinforcing previous findings by Amnesty International and others that the extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention of Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other predominantly Muslims in Xinjiang may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity. It also documented allegations of torture or other ill- treatment, incidents of sexual and gender- based violence, forced labour and enforced disappearances, among other grave human rights violations.