USA: Racial Bias As South Carolina Execution Set

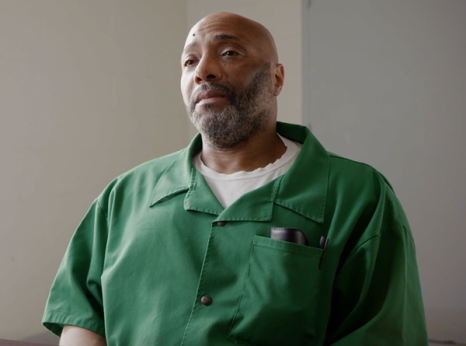

In the early hours of 16 September 1999, the clerk in a convenience store in Spartanburg, South Carolina, was fatally shot and a money bag stolen. A customer playing video poker in the store said Richard Moore shot at him, but he was not struck. Soon afterwards, a short distance away, a police officer arrested Richard Moore who was himself bleeding profusely from a gunshot wound to his left shoulder. The money bag was recovered from his car.

Richard Moore was unarmed when he entered the store. Witnesses testified that the clerk carried a gun when he worked late, and the owner of the store kept several guns under the counter. Two guns were fired during the incident. When arrested soon after the shooting, Richard Moore did not resist, saying, “I did it, I did it, I give up, I give up”. He did not testify at the trial, but at a hearing in 2011, he testified that the clerk had pulled a gun on him, that they struggled for the weapon, and that he, Moore, fired “blindly” at him. A crime scene reconstruction expert retained by the appeal lawyers concluded in 2017 that “the forensic evidence is consistent with Moore’s testimony that he responded to the victim pulling a weapon on him and a shootout ensued but contradicts [the customer]’s testimony that Moore had possession of a gun before the first shot was fired and that Moore fired that shot at [the customer]”. Richard Moore has always denied shooting at the customer in the store.

In her 2022 dissent, state Supreme Court Justice Kaye Hearn wrote that the case “highlights many of the pitfalls endemic to the death penalty, beginning with the role race plays”. The victim was white. Richard Moore is Black. After his arrest but before his trial, there was an election campaign for 7th Circuit Solicitor (covering Spartanburg and Cherokee Counties), during which the challenger was accused by the incumbent of being weak on the death penalty. The latter had a history of seeking death sentences in cases involving white victims: during his tenure from 1985 to 2001, the 7th Circuit pursued the death penalty in 21 cases, in 20 of which the victim was white. The incumbent Solicitor lost the election, but while still in post filed notice that the death penalty would be sought in the Moore trial.

Jury selection for Richard Moore’s trial began on 15 October 2001. Of the original jury pool of 300 people, 65 individuals were Black. Of the 96 individuals who were individually questioned, 19 were Black. A list of 38 qualified jurors was drawn up, only three of whom were Black. The only two Black people questioned before 12 jurors and two alternates (all white) were selected were peremptorily dismissed by the prosecution. Richard Moore’s appeal lawyers have a petition pending before the US Supreme Court arguing that the prosecution engaged in disparate and excessive questioning of the prospective Black jurors compared to white potential jurors, and that the purportedly “race-neutral” reasons the prosecution gave for the removal of the two Black individuals do not survive scrutiny and show that the jury was empanelled in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the US Constitution.

The entire trial lasted four days with the jury finding Richard Moore guilty of murder, assault with intent to kill, armed robbery, and possession of a firearm during the commission of a violent crime and voting for the death penalty. In 2015, several jurors were interviewed for the appeal lawyers. The woman who served as the foreperson of the jury described herself as a proponent of “an eye for an eye” approach to punishment. One of the male jurors described Richard Moore as “the scum of the earth”, and said “the world has no place for people like [him]”.

In 2022, the state Supreme Court ruled that the death sentence was not disproportionate. Justice Hearn accused her colleagues of wrongly “rejecting the significance of Moore’s unarmed status upon entering the store” and “completely los[ing] sight of the vast difference between a ‘robbery gone bad’ and a planned and premeditated murder”. Justice Hearn said she had been unable to find “any other case involving a defendant receiving the death penalty where he entered the place of business unarmed” and noted the “stunning admission” by the state at oral argument that it could not point to any case in South Carolina with this “distinguishing fact”.

The UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), the expert body established under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, ratified by the USA in 1992) to monitor compliance with that treaty, has said that the phrase in Article 6, “the most serious crimes” – which, pending abolition, are the only crimes for which the death penalty may be imposed – “must be read restrictively and appertain only to crimes of extreme gravity involving intentional killing”. Article 6 also prohibits the arbitrary deprivation of life. The HRC emphasises that “arbitrariness” must be interpreted “to include elements of inappropriateness, injustice, lack of predictability and due process of law, as well as elements of reasonableness, necessity and proportionality.” It has also made clear that “death sentences must not be carried out as long as international interim measures requiring a stay of execution are in place”. The IACHR issued precautionary measures in Richard Moore’s case on 4 July 2023, having found a prima facie case of international law violations, requiring a stay to allow it time to decide on the merits of the case.

There have been 19 executions in the USA this year, and 1,601 since 1976. South Carolina accounts for 44 of these executions, including one in 2024. Amnesty International opposes the death penalty in all cases, unconditionally.