Uyghur academic reappears on state broadcast

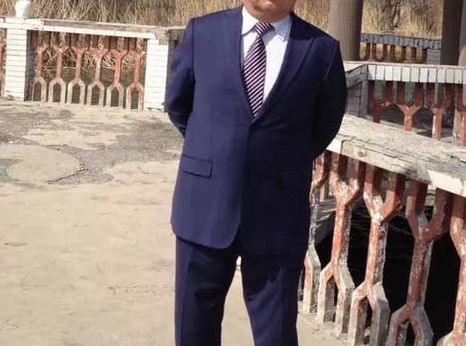

Iminjan Seydin was a history professor at the Xinjiang Islamic Institute and the founder of Xinjiang Imin Book Publishing Company. Since 2012, he has published over 350 books on topics including science, psychology, linguistic education and child education. He has dedicated himself to strengthening cultural exchange.

Iminjan Seydin went missing in May 2017 while part of a working group on poverty alleviation with the Xinjiang Bureau of Religious Affairs in Hotan. It was previously reported that Iminjan Seydin had been sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment for “inciting extremism” in a secret trial in February 2019 in relation to an Arabic rhetoric book that he published in 2014. The Xinjiang Islamic Institute reportedly terminated its contract with him. His daughter, Samira Imin, is currently working at Harvard Medical School.

After being held incommunicado for three years, Iminjan Seydin suddenly reappeared in a video published by the state-run English newspaper China Daily on 4 May 2020, during which he claimed that he had not been “illegally detained” and that his daughter was deceived by “anti-China forces”. Two days later, he finally had a video chat with his daughter in which he told her that he had not contacted her because he had gone for work all this time and he wanted to really focus on what he was doing.

In the video chat, Iminjan Seydin’s daughter grew suspicious that her father was being closely monitored by the authorities because of his repeated praise for China and the Communist Party. Under these circumstances, she is worried that the communication with her father could be cut off anytime.

Uyghurs are a mainly Muslim ethnic minority group who are concentrated primarily in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) in China. Since the 1980s, the Uyghurs have been the target of systematic and extensive human rights violations. These include arbitrary detention and imprisonment, incommunicado detention and restrictions on religious freedom as well as cultural and social rights. Local authorities maintain tight control over religious practice, including prohibiting all government employees and children under the age of 18 from worshiping at mosques. Chinese government policies limit the use of the Uyghur language, impose severe restrictions on freedom of religion and encourage sustained influx of Han migrants into the region.

Media reports have illustrated the extent of new draconian security measures implemented since Chen Quanguo came into power as Xinjiang’s Party Secretary in 2016. In October 2016, there were numerous reports that authorities in the region had confiscated Uyghur passports in an attempt to further curtail their freedom of movement. In March 2017, the Xinjiang government enacted the “De-extremification Regulation” that identifies and prohibits a wide range of behaviours labelled “extremist”, such as “spreading extremist thought”, denigrating or refusing to watch public radio and TV programmes, wearing burkas, having an “abnormal” beard, resisting national policies, and publishing, downloading, storing, or reading articles, publications, or audio-visual materials containing “extremist content”. The regulation also set up a “responsibility system” for government cadres for “anti-extremism” work and established annual reviews of their performance.

It is estimated that up to a million Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other predominantly Muslim people have been held in the “transformation-through-education” centres. The Chinese authorities had denied the existence of such facilities until October 2018, when they began describing them as voluntary, free “vocational training” centres. They claim that the objective of this vocational training is to provide people with technical and vocational education to enable them to find jobs and become “useful” citizens. China’s explanation, however, contradicts reports of beatings, food deprivation and solitary confinement that have been collected from former detainees.

China has rejected calls from the international community, including Amnesty, to allow independent experts unrestricted access to Xinjiang. Instead, China has made efforts to silence criticism by inviting delegations from different countries to visit Xinjiang for carefully orchestrated and closely monitored tours.